Politicians often try to empathize with struggling Americans by promising to cut government spending, “just like regular households in tough times.” This simile evokes different reactions depending on one’s economic views. Keynesians think it’s reckless, proponents of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) think it’s absurd, and Rothbardians think it’s correct as far as it goes, but it falsely equates tax revenues to an honest living.

In this context, I was amazed to read a CNBC article earlier this week arguing that households were no role models for the politicians! It’s worth going through a comparison to clarify the important issues.

Households a Bad Role Model for Government?

The article (which originally ran on Reuters) sets the stage:

Republicans, claiming revulsion over the U.S. government’s $14.3 trillion in debt, say Washington needs to take a hard look at its finances and balance the books like the typical American family.

“It’s simple. Spend what you take in. That’s what every family has to do … imagine the federal government actually doing what makes sense,” said U.S. Representative Jim Jordan, a prominent conservative Republican.

Jordan is among a string of politicians who say the nation’s mounting debt can be resolved with a simple dose of prudent planning.

Although appealing to average voters, such rhetoric often annoys professional economists. For example, Keynesians argue that when the private sector is trying to wind down debt, the only way to maintain aggregate demand is for the government to run offsetting deficits.

Proponents of MMT would go even further, arguing that the analogy with households is simply an anachronism in our age of fiat money. The MMT position is that modern governments are never constrained by fiscal matters, since they can issue their own currency. The only problem with the government spending too much would be increasing price inflation, not an inability to finance the spending.

What is interesting is that the Reuters/CNBC article also objected to Jim Jordan’s analogy, but for different reasons. To wit, the article argued that households were no role models when it came to financial management:

But in looking for ways to balance its budget, policymakers may want to avoid taking cues from American families.

According to the latest Federal Reserve statistics, U.S. consumer credit is at about $2.4 trillion for short- and intermediate-term borrowing on credit cards and for car loans, vacations, boats and college loans. That did not count the trillions of dollars in borrowing for home mortgages.

Americans are juggling about $796 billion in credit card debt alone, according to the statistics.

The average credit card debt per U.S. household is $8,329, Hardekopf said, quoting a March Nilson Report. That figure rises to $10,679 when only households that actually have credit cards — about 75 percent — were factored in, he said.

It’s no wonder there’s a bumper sticker out there asking:

“Can I pay my Visa with my Master Card?”

The National Foundation for Credit Counseling conducts an annual “financial literacy” survey that tracks consumers’ borrowing habits and financial worries.

Its latest survey, carried out last March by Harris Interactive, found only 43 percent of families said they had a household budget and kept close track of how much they spent on food, housing and entertainment.

Fifty-six percent said they didn’t have any budget at all.

And, according to the NFCC survey, while 68 percent said they paid their bills on time, many apparently were not paying off their entire credit card bills each month.

Forty percent said they carried credit card debt from month to month, while half said they did not. A whopping 73 percent said they were worried about their financial situation.

As we’ll see, these statistics miss the point of the comparison.

When Times Are Tough, the Proper Move Is to Cut Spending

Of course, politicians of all stripes mouth platitudes while failing to enact policies living up to their rhetoric. But in this case, the rhetoric itself is correct: Just as most American households are much more careful about their finances now than they were during the housing-bubble years, so too should the government be.

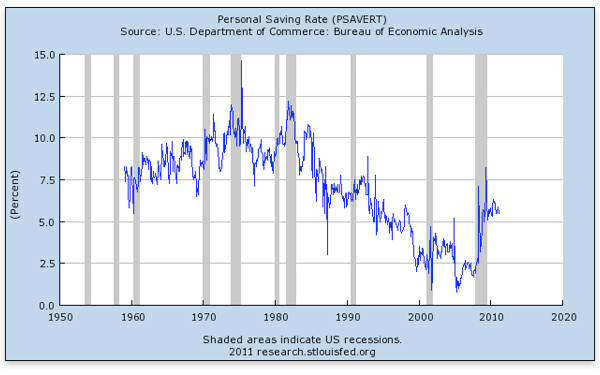

Most of the statistics quoted above merely convey that households have debt. But that’s not the issue — the government has a massive amount of debt as well. The difference is that once the housing bubble burst and everyone realized Americans had been living beyond their means for years, the average household changed its ways. That is, savings rates shot way up, and households began paying down their debt:

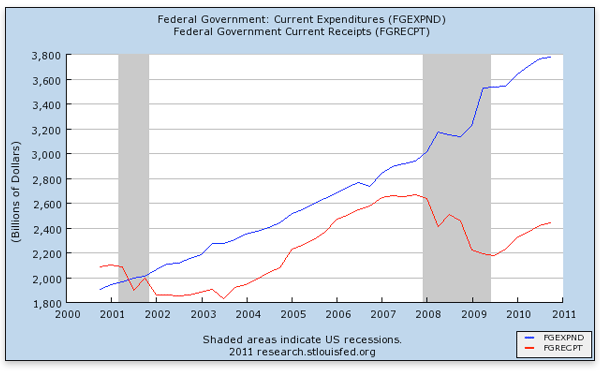

Of course, the federal government has just done the opposite. Even while Presidents Bush and Obama both acknowledged that excessive leverage and overconsumption were problems during the housing bubble years, and even as revenues plunged, this is what happened to spending on their respective watches:

There Are Solid Reasons to Support “Fiscal Austerity”

As I argued in my book on the Depression, the federal government didn’t engage in “countercyclical policies” too much before the allegedly laissez-faire Herbert Hoover. Sure, the government would run up massive debts during wartime, but it would then pay them down. Indeed, Calvin Coolidge ran a surplus every year of his presidency.

In fact, as Tom Woods and I have pointed out repeatedly, the Depression of 1920–21 provides a textbook example of the Fed engaging in “tight-money” policies while the federal government engaged in (what are now almost) inconceivably aggressive budget cuts. The result was a short, painful, deflationary depression, followed by a decade of immense prosperity.1 There are other, more recent examples of debt-ridden governments slowing or even cutting spending in order to eliminate budget deficits and improve economic growth.

Conclusion

In one sense, the analogy between households and the government is flawed: Households (generally) earn their income through voluntary transactions in which they provide goods and services to others. In contrast, the government raises the revenue with which to provide its “services” ultimately through the threat of imprisonment.

Even so, the deficit-hawk politicians are right when they say the government should be sharing in the belt-tightening along with everyone else. Slashing spending at the federal level would return much-needed resources to the private sector, where they would do the most good.

- 1Keynesian sympathizer Daniel Kuehn has argued that Woods and I are wrong to think the 1920–21 episode bears much relevance for today.