A September 21 announcement by the G-7 finance ministers endorsed less intervention in the foreign exchange market, and triggered a large sell-off of the US dollar. On the day of the announcement, in relation to the end of August, the US currency fell by 4.8% against the Euro and 4.1% against the Yen.

Many economists have suggested that the weakening in the US dollar could actually be good for the economy—since a weaker dollar will boost manufacturing production, which in turn will lift employment and all this will set in motion economic growth. It follows then that the US dollar devaluation is exactly what is needed to keep the US economy going.

The popular way of thinking

According to popular thinking the key to economic growth is demand for goods and services. It is held that increases in demand for goods and services gives rise to economic growth by triggering the production of goods and services. Increases or decreases in demand for goods and services are behind rises and declines in the economy’s production of goods. Hence in order to keep the economy going economic policies must pay close attention to overall demand.

Now, part of the demand for domestic products emanates from overseas. The accommodation of this demand is labelled exports. Likewise, local residents exercise demand for goods and services produced overseas, which is labelled imports. Note that while an increase in exports gives rise to overall demand for domestic output, an increase in imports weakens demand. Hence exports, according to this way of thinking, are a factor that contributes to economic growth while imports are a factor that detracts from the growth of the economy.

Because overseas demand for a country’s goods and services is an important ingredient in setting the pace of economic growth, it makes sense to make locally produced goods and services attractive to foreigners. One of the ways to make domestically produced goods more in demand by foreigners is by making the prices of these goods more attractive.

For instance, the price of an identical bag of potatoes in the US is $10 and 10 Euro’s in Europe. Also, the exchange rate between the US dollar and the Euro is 1:1 i.e. one–to–one. At the exchange rate of 1 Euro to $1 a European can get for his 10 Euro one American bag of potatoes.

One of the ways of boosting their competitiveness is for Americans to depreciate the US dollar against the Euro. Let us assume that in response to a Fed announcement that it will drastically loosen its monetary stance, the rate of exchange falls to 0.5 Euro per $1. Consequently, this will mean that $10 is now worth 5 Euro, which in turn implies that an American bag of potatoes in Europe is offered for 5 Euro. Consequently, a European can now purchase for 10 Euro two American bags of potatoes instead of one before the depreciation of the US dollar. In other words, the purchasing power of Europeans with respect to American potatoes has doubled.

If we were to apply the potatoes example to all goods and services, one can reach the conclusion that as a result of currency depreciation, all other things being equal, the overall demand for domestically produced goods is likely to increase. This in turn will give rise to a better balance of payments and in turn to stronger economic growth. Observe that to lift foreigners’ demand, Americans are now effectively offering two bags of potatoes for one European bag of potatoes. This also means that the price of the European bag of potatoes in the US is now twice what it was before the depreciation of the US dollar. This most likely will lower American’s demand for European potatoes. What we have here, as far as the US is concerned, is more exports and fewer imports, which according to mainstream thinking is great news for economic growth.

Equally, at the original exchange rate of 1:1 a reduction in the domestic price of US potatoes from $10 to $5 would also enable a European to exchange his 10 Euro for two bags of potatoes. In short, changes in the exchange rate or changes in prices in respective countries will determine so-called international competitiveness, which is also labelled as the real exchange rate. This can be summarized as:

Real exchange rate = (domestic prices/foreign prices)*exchange rate

The exchange rate is the number of foreign currency per unit of local currency.

According to this expression, a fall in the real exchange rate implies growing competitiveness and a rise means falling international competitiveness. Hence, following this expression, currency depreciation (a fall in the number of foreign currency exchanged per local currency) will lead to a fall in the real exchange rate and thus to an increase in international competitiveness.

A fall in foreign prices, however, will lift the real exchange rate and therefore reduce competitiveness. In this way of thinking, it is quite clear that currency depreciation—all other things being equal—is beneficial for economic growth.

For instance, in their research study of the Mexican economy, Dornbusch and Werner have concluded that: “If the currency is not devalued, growth will not keep pace with the growth of the labor force; the divisions in Mexican society will widen; and national stability will be threatened.”1

Furthermore, according to Dornbusch and Werner, “…recent major devaluations in Finland, Sweden, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom did not lead to inflation—in fact, it has come down, as have interest rates. Devaluation was a boon to these countries.”2

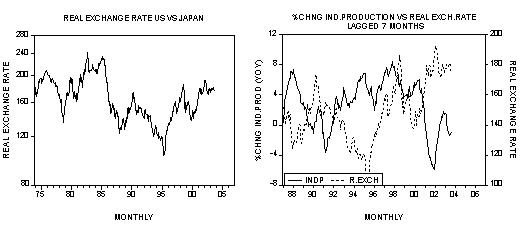

It seems that the message conveyed by the real exchange rate equation tends to confirm the experience in the US. Thus since 1999 US competitiveness viz. Japan has been steadily falling. The real exchange rate, which stood at 138 in November 1999 jumped to 176 in August 2003. The fall in competitiveness during this period was associated with a sluggish economy. In short, the data seems to support the view that a rising real exchange rate may be an important contributing factor to currently subdued economic growth.

Moreover, our statistical analysis indicates that the lagged growth momentum of the real exchange rate displays good visual inverse correlation with the growth momentum of industrial production. An increase in the growth momentum of the real exchange rate (deterioration in US competitiveness) is followed by a fall in the growth momentum of industrial production. A fall in the growth momentum of the real exchange rate (improvement in US competitiveness) is followed by an increase in the growth momentum of industrial production.

It seems, therefore, that it makes a lot of sense to depreciate the US dollar in order to revive the economy.

Why boost in exports due to currency depreciation cannot grow the economy

When a central bank announces a loosening in its monetary stance, this leads to a quick response by the participants in the foreign exchange market through selling the domestic currency in favor of other currencies, thereby leading to domestic currency depreciation. In response to this, various producers now find it more attractive to boost their exports. In order to fund the increase in production, producers approach commercial banks, which on account of a rise in central bank monetary pumping are happy to expand their credit at lower interest rates.

By means of new credit producers can now secure resources required to expand their production of goods in order to accommodate growing overseas demand. In other words, by means of newly created credit producers divert real resources from other activities. As long as domestic prices remain intact, exporters will record an increase in profits.

However, the so-called improved competitiveness on account of currency depreciation means that the citizens of a country are now getting less real imports for a given amount of real exports. In short, while the country is getting rich in terms of foreign currency, it is getting poor in terms of real wealth, i.e., in terms of the goods and services required for maintaining peoples’ life and well-beings. As time goes by however, the effects of loose monetary policy filters through a broad spectrum of prices of goods and services and ultimately undermine exporters profits. In short, a rise in prices puts to an end the illusory attempt to create economic prosperity out of thin air. According to Ludwig von Mises,

The much talked about advantages which devaluation secures in foreign trade and tourism, are entirely due to the fact that the adjustment of domestic prices and wage rates to the state of affairs created by devaluation requires some time. As long as this adjustment process is not yet completed, exporting is encouraged and importing is discouraged. However, this merely means that in this interval the citizens of the devaluating country are getting less for what they are selling abroad and paying more for what they are buying abroad; concomitantly they must restrict their consumption. This effect may appear as a boon in the opinion of those for whom the balance of trade is the yardstick of a nation’s welfare. In plain language it is to be described in this way: The British citizen must export more British goods in order to buy that quantity of tea which he received before the devaluation for a smaller quantity of exported British goods.

Contrast the policy of currency depreciation with a conservative policy where money is not expanding. Under these conditions, when the pool of real wealth is expanding, the purchasing power of money will follow suit. This, all other things being equal, will lead to currency appreciation. With the expansion in the production of goods and services and falling prices and thus production costs, local producers can improve their competitiveness and profitability in overseas markets while the currency is actually appreciating. Within the framework of loose monetary policy exporters’ temporary gains are at the expense of other activities in the economy, within the framework of a tight monetary stance gains are not at any one’s expense but just the manifestation of real wealth generation.

Can currency depreciation take place in a free market?

The entire issue of the alleged benefits of currency depreciation is only of relevance in a hampered market where paper money is enforced by the government through its central bank. In a free-market economy, there cannot be such a thing as currency depreciation, which supposedly can grow the economy.

Within the free market, there cannot be currency depreciation as such. Since in a true free-market economy money is gold, there cannot be an independent entity such as a “dollar.” Prior to 1933, the name “dollar” was used to refer to a unit of gold that had a weight of 23.22 grains. Since there are 480 grains in one ounce, this means that the name dollar also stood for 0.048 ounce of gold. This in turn, means that one ounce of gold referred to $20.67. Now, $20.67 is not the price of one ounce of gold in terms of dollars as popular thinking has it, for there is no such entity as a dollar. Dollar was just a name for 0.048 ounce of gold. On this Rothbard wrote, “No one prints dollars on the purely free market because there are, in fact, no dollars; there are only commodities, such as wheat, cars, and gold.3

Likewise, the names of other currencies stood for a fixed amount of gold. The habit of regarding these names as a separate entity from gold emerged with the enforcement of the paper standard. Over time, as paper money assumed a life of its own, it became acceptable to set the price of gold in terms of dollars, francs, pounds, etc. The absurdity of all this reached new heights with the introduction of the floating-currency system.

In a free market, currencies do not float against each other. They are exchanged in accordance with a fixed definition. If the British pound stands for 0.25 of an ounce of gold and the dollar stands for 0.05 ounce of gold, then one British pound will be exchanged for five dollars. This exchange stems from the fact that 0.25 of an ounce is five times larger than 0.05 of an ounce, and this is what the exchange of 5-to-1 means.

In other words, the exchange rate between the two is fixed at their proportionate gold weight, i.e., one British pound = five US dollars. The absurdity of a floating currency system is no different from the idea of having a fluctuating market price for dollars in terms of cents. How many cents equal one dollar is not something that is subject to fluctuations. It is fixed forever by definition. 4

The present floating exchange rate system is a byproduct of the previously discredited Bretton Woods system of fixed currency rates of exchange, which was in operation between 1944 to 1971. Within the Bretton Woods system the US dollar served as the international reserve currency upon which all other currencies could pyramid their money and credit. The dollar in turn was linked to gold at $35 per ounce. Despite this supposed link to gold, only foreign governments and central banks could redeem their dollars for gold.

A major catalyst behind the collapse of the Bretton Woods system was the loose monetary policies of the US central bank which pushed the price of gold in the gold market above the official $35 per ounce. The price, which stood at $35/oz in January 1970 jumped to $43/oz by August 1971 – an increase of almost 23%. The growing margin between the market price of gold and the official $35 per ounce (see chart) created enormous profit opportunity, which some European central banks decided to exercise by demanding the US central bank redeem dollars for gold.

Since Americans didn’t have enough gold to back up all the printed dollars, they had to announce effective bankruptcy and cut off any link between dollar and gold as of August 1971. In order to save the bankrupt system policymakers have adopted the prescription of Milton Friedman to allow a freely floating standard.

While in the framework of the Bretton Woods system the dollar had some link to the gold and all the other currencies were based on the dollar, all that has now gone. In the floating framework there are no more limitations on money printing. According to Murray Rothbard:

One virtue of fixed rates, especially under gold, but even to some extent under paper, is that they keep a check on national inflation by central banks. The virtue of fluctuating rates—that they prevent sudden monetary crises due to arbitrarily valued currencies—is a mixed blessing, because at least those crises provided a much-needed restraint on domestic inflation.

Through policies of coordination, central banks maintain synchronized monetary pumping so as to keep the fluctuations in the rate of exchanges as stable as possible. Obviously, in the process such policies set in motion, a persistent process of impoverishment through consumption is not backed up by production of real wealth.

Furthermore, within this framework, if a country tries to take advantage and depreciate its currency by means of a relatively looser monetary stance this runs the risk that other countries will do the same. Consequently, the emergence of competitive devaluations is the surest way of destroying the market economy and plunging the world into a period of crisis.

On this Mises wrote, “A general acceptance of the principles of the flexible standard must therefore result in a race between the nations to outbid one another. At the end of this competition is the complete destruction of all nations’ monetary systems.”

- 1Dornbusch R. and Werner A. 1994. “Mexico, stabilization. Reform and no growth,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Vol 1, pp, 253–315.

- 2Ibid.

- 3Murray N. Rothbard. “The Case for a Genuine Gold Dollar,” in Llewellyn H. Rockwell, Jr., The Gold Standard: An Austrian Perspective (Lexington, Mass: D.C. Heath, 1985), pp. 1–17.

- 4Ibid.