In 1912, Ludwig von Mises wrote,

“[T]he sound-money principle has two aspects. It is affirmative in approving the market’s choice of a commonly used medium of exchange. It is negative in obstructing the government’s propensity to meddle with the currency system.”1

And further:

“It is impossible to grasp the meaning of the idea of sound money if one does not realize that it was devised as an instrument for the protection of civil liberties against despotic inroads on the part of governments. Ideologically it belongs in the same class with political constitutions and bills of right.”2

Today’s national money regimes bear no resemblance to Mises’s sound-money principle. The quantity and quality of money is no longer a free-market phenomenon; it is determined by government-controlled central banks.

To prevent governments from misusing their coercive power in monetary affairs, two “institutional arrangements” have been put into place.

First, central banks have been made politically independent to prevent politicians from trying to trade off benefits resulting from an inflation-induced, short-term, cyclical upswing against the medium- to long-term costs resulting from the debasing of the means of payments.

Second, central banks have been explicitly or implicitly assigned the objective of maintaining “price level stability.” This is because inflation is widely seen as a societal evil; and a “stable price level” is considered conducive to improving growth and increasing the number of jobs.

From the Austrian point of view, today’s money regimes — even when taking into account the protections against government monetary mismanagement — would be incompatible with Mises’s principle of sound money. In fact, Austrians consider today’s monetary order a serious threat to the free societal order.

The Origin of Money

The starting point for Austrians’ critical reflection is the economic origin of money. Historical experience shows that money, the means of exchange, emerged from free-market forces. People learned that moving from direct (barter) trade to indirect trade — that is exchanging vendible goods against a good that might not necessarily be demanded for consumption or production in the first place — allows a higher standard of living.

Driven by peoples’ self-interest and the insight that directly traded goods possess different degrees of marketability, some market agents start demanding specific goods not for their own sake (consumption or production) but for the sake of using them as a medium of exchange.3 Doing so entails a number of advantages.

For instance, if money is used as a means of exchange there does not have to be a “double coincidence of wants” to make trade possible. In a barter economy, it would take Mr. A to demand the good Mr. B has to offer, and Mr. B to demand the good that Mr. A wants to exchange.

By accepting not only directly useful goods needed in terms of consumption and production, but also goods with a higher marketability than those surrendered, individuals can benefit more fully from the economic advantages under a division of labor and free trade.

With more and more people using a medium of exchange in trading a universally employed medium of exchange emerged: money. Experience shows that it was mostly gold (and, to a lesser extent, silver) that became the internationally accepted means of exchange. In that sense, money must naturally emerge from a commodity.

Money as a Commodity

Over time, market agents preferred holding the most marketable commodity over those of less marketability: “there would be an inevitable tendency for the less marketable of the series of goods used as a media of exchange to be one by one rejected until at least only a single commodity remained, which was universally employed as a medium of exchange; in a word, money.”4

It is against the background of such reasoning that Mises put forward his “regression theorem,” which holds that “no good can be employed for the function of a medium of exchange which at the very beginning of its use for this purpose did not have exchange value on account of other employments.”5

Today, however, the universally accepted means of exchange is government-controlled paper, or fiat, money. It is not backed by, or related to, a scarce commodity freely chosen by the market. So how did an intrinsically worthless piece of paper issued by governments acquire the status of money?

The Ideologically Rooted Aversion to the Interest Rate

The explanation might be found with peoples’ ideologically rooted, deep-seated aversion to the interest rate. The lower the interest rate, so the thinking goes, the better it is for output and employment. A government-controlled money supply monopoly — in contrast to free market money — offers the possibility of “public opinion” dictating the desired level of interest rates.

Having obtained a money-supply monopoly, a government-controlled central bank can, at will and at any time, expand credit and money supply relative to is demand, thereby pushing down the interest rate — something that wouldn’t be possible (to such a degree) under free-market money.

That said, the public’s wish for low interest rates explains why governments were allowed to sever the “anchoring” of established “money substitutes” — defined as paper titles backed by commodity money (gold) — thereby making possible today’s government-controlled paper-money order.

Under the gold standard, money “circulated” in the form of gold (that is standardized bars of bullion and gold coins) and claims to specified amounts of gold deposited with banks. Circulating commodity-backed paper money resulted simply from a free choice on the part of money users to economize on the costs of storing and transacting money.

Holding money in the form of gold (coins) and paper claims to gold increased the convenience on the part of money users. To be sure, such an arrangement did not change the overall supply of money; nor did it affect the distribution of income and wealth among individual market agents. The paper just represented an unconditional claim to money (gold), redeemable at any time.

In many countries occasional departures from a fixed link of money to gold had occurred, but the link was finally eliminated on 15 August 1971 when US President Richard M. Nixon “closed the gold window,” terminating the obligation that the United States had assumed under the System of Bretton Woods to convert US dollars held by foreign monetary authorities into gold at the fixed price of US$35. “Before 1971, every major currency from time immemorial had been linked directly or indirectly to a commodity.”6

Deprived of its claim to the underlying commodity, an already established paper money does not necessarily lose its money function (straight away). Mises wrote,

“Before an economic good begins to function as money it must already possess exchange-value based on some other cause than its monetary function. But money that already functions as such may remain valuable even when the original source of its exchange-value has ceased to exist.”7

The important insight is, however, that government paper money can only be established by a fraudulent act on the part of the government.

The Impossibility of a Stable Purchasing Power of Money

Austrians maintain that human action in a free society is characterized by ongoing change. In a market economy, people continually choose among alternatives. This entails ever-changing valuations of goods and services. Searching for absolute stability of vendible items’ exchange ratios is therefore a futile undertaking. This applies to the exchange value of all kinds of goods and services, including money.

Money is subject to peoples’ actions and valuations in the same way that all other economic goods and services are. As a result, money’s subjective and objective exchange values continually fluctuate as well, and there is no such a thing as the stability of the exchange ratio of money vis-à-vis other goods and services.

For instance, to satisfy an increase in the demand for money, people would be required to surrender more goods and services. A higher supply of vendible goods against a given money supply, in turn, would lower the exchange value of the former against the latter. As a result, the exchange value of money rises.

To illustrate, consider a market in which money is supplied and demanded against a vendible good. Chart (a) shows the demand for a good (equalling the supply of money) and its supply (equalling the demand for money). In equilibrium (point A), the exchange ratio of money units per good is P0, and the market clearing amount of goods is Y0.

Assuming a given supply of goods (that is a constant demand for money), an increase in the demand for goods (that is an increase in money supply) pushes the exchange ratio of money units against goods from P0 to P1 (point B). As a result, an increase in the supply of money relative to the goods supply leads to a loss in the exchange value of the means of exchange.

Increasing Money Supply is Inflation

From the Austrians’ viewpoint, any change in money supply influences money’s exchange ratio, irrespective of whether a commodity or fiat money standard is in place. Take, for instance, a gold standard regime, in which money supply increases (say, through mining). Additional money is exchanged against goods in certain sectors of the economy. As a matter of fact, the first users of the newly created money spend it on goods and services given prevailing market prices.

As more and more market agents get hold of additional money, however, the marginal utilities of money in peoples’ portfolios decline, whereas the marginal utility of non-monetary goods and services increases. In an attempt to return to equilibrium, people offer more money against goods and services. Money prices rise as each money unit can now buy fewer goods and services when compared with the situation before the stock of money increased.

Against this background it is quite obvious why Mises defined inflation as an increase in money supply — and deflation as a decline in money. Whereas inflation is, from the Austrian point of view, inherent in any money supply regime, they opt for free-market money. This is because such a monetary regime is considered much less inflation prone compared to government controlled money.

Today’s Definition of Inflation

Needless to say, Mises’s definition stands in stark contrast to today’s interpretation of the terms:

“What many people today call inflation or deflation is no longer the great increase or decrease in the supply of money, but its inexorable consequences, the general tendency towards a rise or a fall in commodity prices and wage rates.”8

Mainstream economics defines inflation as the persistent rise in the economy’s price level. Such a definition is based on an index regime according to the work of Irving Fisher (1867–1947). Today, price-level stability is typically understood as an economy’s price level rising by around 2% on an annual basis. If inflation remains around this level, people are said to enjoy “price stability.”

However, any inflation definition related to Fisher’s index concept is economically and politically deceiving and erroneous. The economic truth is that even an unchanged (consumer) price index may well be accompanied by a loss in the exchange value of money.

Government-made Crisis

To show this assume, for instance, the demand for money (representing the supply of goods) rises. Starting from an equilibrium represented by point A in Chart (b), this would move to the money demand schedule to the right, lowering the money units per goods from P0 to P1.

In an attempt to keep constant the exchange value of a money unit against the good, the central bank would have to increase the stock of money. By doing so, it would move the money-supply schedule (that is the demand for goods) to the right. As a result, the exchange ratio of money vis-à-vis vendible goods rises back to P0.

Under the price-level-stability objective, money holders are de facto deprived from enjoying any (productivity related) increases in the exchange value of money. Borrowers, in contrast, benefit: central bank action prevents their nominal incomes from declining — as would be the case in an unhampered free market situation.

Furthermore, government induced changes in the stock of money affect different sectors of the economy to different degrees and at different points in time. This, in turn, might well entail distortions in the economy’s relative price mechanism, which encourages malinvestment, cyclical swings of the economy, stock market crashes, and losses in output and employment. It doesn’t take much to expect that any such crisis would provoke the public calling upon the government to solve the crisis.

Typically, additional government action, rather than free-market forces, is seen as a solution to economic hardship, which had actually been triggered by government meddling in monetary affairs. The public calls for even more interventions — that is even lower interest, for increasing credit and money supply even further — thereby leading farther and farther away from the ideal of the free society, ultimately ending in a complete destruction of the value of money (”hyperinflation”).

The Call for Free-market Money

Austrians’ great concern is that a government-run money-supply regime would ultimately end in economic and political disaster: the ruin of money and, with it, of the free societal order. It is in particular against this background that they call for ending the government money-supply monopoly and returning to free-market money.

Under a freely chosen commodity-based money regime such as, for instance, the gold standard, money supply would tend to increase relatively predictably and in relatively small quantities over time — compared with random, arbitrary, and usually dramatic increases in paper-money supply.

It might sound paradoxical to most mainstream economists, but to Austrians it is the very objective of price stability that contributes strongly to making a dismal prediction. The “index regime” provokes repeated government intervention and misalignments, which, sooner or later, result in serious economic and societal crises.

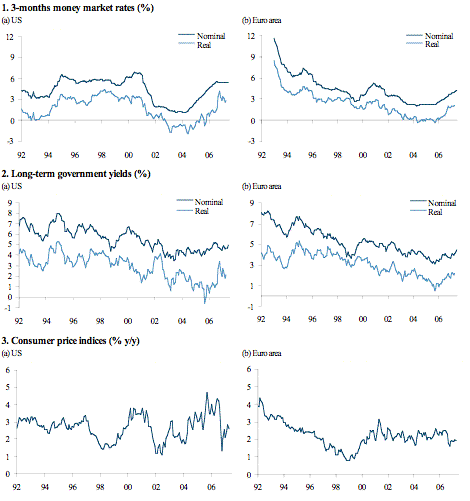

So what do the data say about Austrians’ concerns? Charts 1 (a) and (b) show the 3-months interest rates in the United States and Germany (the euro area from 1 January 1999) from January 1992 to April 2007 in nominal and real terms. In both currency areas, short-term rates — set by central banks — have been drifting lower over time. The downward trend is even more visible in long-term yields, as shown in Charts 2 (a) and (b).

The lowering of central bank rates might have been encouraged by relatively low consumer price inflation, which represents central banks’ target variables (see Charts 3 (a) and (b)). By reducing the costs of borrowing, bank credit has been allowed to expanding rather strongly. The increase in credit and money supply has not been lost upon prices.

The growth rates of bank credit and stock market prices appear to be rather closely related (see charts 4 (a) and (b)). Such a finding could suggest that the increase in credit and money might have (so far) pushed up stock (asset) prices rather than consumer price inflation. If such a development has not been overcompensated by declines in prices of other goods, the exchange value of money must have declined.

Finally, charts 5 (a) and (b) plot annual bank credit growth against GDP expansion. In both currency areas, an increase (slowdown) in credit supply growth seems to have been accompanied by rising (declining) output. Even more important, the rise in output keeps falling short of the increase in credit supply, and this is a clear indication that the economies’ debt burdens are on the rise.

Having abandoned the sound-money principle, governments’ central banks are in the very process of forcing down the interest rate over time, by way of strongly expanding credit and money supply. This, in turn, leads to asset price inflation, misallocation of scarce resources, inducing cyclical swings (”boom and bust”).

To make things worse, central banks allow credit supply growth to systematically outpace income growth, and so the economies’ overall debt-to-GDP ratios are brought up over time. Such a development is economically unsustainable, even though it might go on for quite some time as the central bank keeps pushing down the interest rate.

As the debt burden rises further and further, however, “public opinion” must sooner or later start calling for debasing of the currency via inflation to get rid of their obligations. Mises knew why abandoning the principle of sound money would be so problematic: “In the opinion of the public, more inflation and more credit expansion are the only remedy against the evils which inflation and credit expansion have brought about.”9

- 1Mises, L. von (1912), The Theory of Money and Credit, Liberty Fund, Indianapolis, p. 454.

- 2Ibid, p. 455.

- 3See Hoppe, H-H. (1994), “How is Fiat Money Possible — or, The Devolution of Money and Credit,” Review of Austrian Economics, 7, No. 2.

- 4Mises, L. von (1912), The Theory of Money and Credit, Liberty Fund, Indianapolis, pp. 32.

- 5Mises, L. von (1996), Human Action, 4th Edition, Fox & Wilkes, San Francisco, p. 410.

- 6Friedman, M. (1994), Money Mischief: Episodes in Monetary History, San Diego, New York, London, p. 15.

- 7Mises, L. von (1912), The Theory of Money and Credit, Liberty Fund, Indianapolis, p. 111.

- 8Mises, L. von (1996), Human Action, 4th Edition, Fox & Wilkes, San Francisco, p. 423.

- 9Ibid, pp. 576.