In virtually all major economies business sentiment indicators are promising additional production and employment gains. Most prominently, international stock market valuations, fueled by brightening expectations of future profitability gains, are regaining lost ground, swiftly moving back towards levels seen before the sharp price correction which set in 2000/01. In fact, the world’s major economies are widely seen as entering a new phase of prosperity.

However, one should not get carried away by widespread euphoria. Taking into account the lessons learned from analyzing monetary matters from the point of view of the Austrian School of Economics, it becomes crystal clear that the very foundations of the monetary system on which economic prosperity of the industrial countries so heavily depends keep deteriorating at a rapid pace.

The latest economic boom phase of the late 1990s (”New Economy”) was accompanied, and even provoked, by an overly expansionary monetary policy. Strong increases in money and credit supply made it possible to finance unprecedented asset price inflation — most notably for stocks, bonds and housing — which inevitably ended in a (this time: relatively mild) collapse. What is even more important, the monetary policy that is to be held responsible for boom and bust has been kept in place, sowing the seeds of the next, presumably even more severe, crisis.

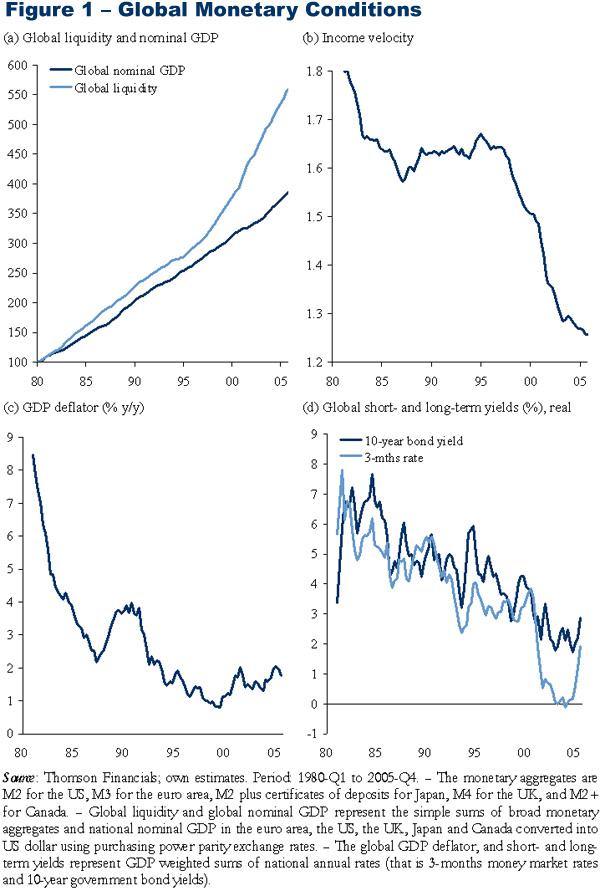

To provide an overview of monetary developments in major industrialized countries, Figure 1 (a) shows global money supply and global nominal GDP. From the early 1980s to the middle of the 1990s, global money supply and global nominal output expanded more or less in parallel. In the period thereafter, however, the former clearly started outpacing the latter.

As a result, the income velocity of money — that is the relation between nominal output and the stock of money — declined sharply (see Figure 1 (b)). Velocity fell from around 1.65 at the end of 1994 to 1.25 at the end of 2005. To put it differently: real money holdings relative to real income have increased substantially since the middle of the 1990s compared to previous periods. Global inflation — when applying the commonly used measures such as the annual rise in the GDP deflator — has remained relatively subdued (see Figure 1 (c)). Short- and long-term real rates (that is nominal rates minus the annual change in the GDP deflator) kept declining throughout the period under review (see Figure 1 (d)).

Of course, data by itself doesn’t talk. Its interpretation requires a theoretical framework. So what is the story behind the findings above? One may think that peoples’ preference for holding a part of their wealth in liquid money deposits has increased, perhaps as a direct result of higher (financial market) uncertainty. As long as the additional money holdings would remain locked in peoples’ purses, the increase in money supply might be less of a source of concern.

But what if money holders consider their money holdings to be “excessive” and decide to reduce their real balances? In such a case, excess money will make itself felt for real and/or nominal magnitudes. Individual attempts to reduce money holdings could initiate another economic upswing as the increase in monetary demand translates into higher investment and consumption spending. However, with money supply in excess of output, inflation should show up sooner or later.

Alternately, there is the possibility that market agents attempt to reduce their excess money holdings by increasing demand for existing (financial) assets, thereby directly triggering renewed global asset price inflation in stock, bond, and/or housing markets. That said, monetary policy action delivered in the past might still hold extremely unpleasant surprises in store. Unfortunately, the unpleasant story doesn’t end here.

Some might find confidence in the fact that major central banks have started raising interest rates or are considering doing so in the near future. However, rate hikes appear to be motivated by, first, monetary policy makers’ desire to bring rates back to a more “normal level” when measured against rate levels seen in the past. Second, central banks want to counter actual and potential “cost push” effects on consumer prices stemming from the latest rise in commodity/energy prices.

Of course, higher borrowing costs should put a dampening effect on money and credit creation. However, and this is important, reigning in money and credit expansion does not rank among the primary objectives of central banks’ monetary policies. In fact, central banks keep gearing their policies towards limiting upward movements of consumer price indices.

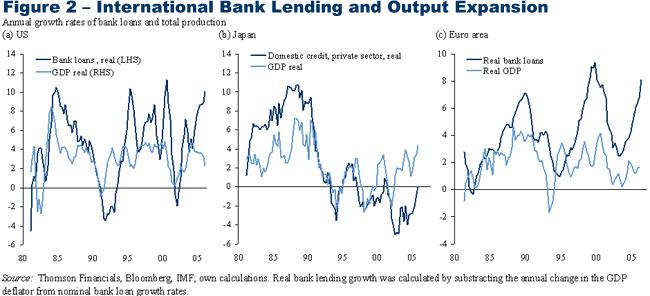

Figure 2 (a) to (c) shows the annual growth of bank loans and real output for the period 1981-Q1 to 2005-Q4. In the United States, bank credit expansion was, on average, well above output gains in the second half of the 1990s. Credit supply growth in excess of production growth was even more pronounced in the euro area. In contrast, credit expansion in Japan was stronger than output growth until the early 1990s. Thereafter the relation reversed (suggesting a “de-leveraging” of private borrowers) as the country experienced a period usually referred to as deflation.

With bank loan expansion rising in excess of output gains cyclical swings of economic activity are set to increase. Additional credit supply is, in a first stage, most likely to initiate an increased level of economic activity. In a second stage, however, the increase in the build up of debt will no longer be matched by expected output gains. With profit and income plans disappointed, investment and consumption will be reduced. The credit driven boom is inevitably followed by bust.

Ludwig von Mises stressed that a credit expansion via additional fiduciary money “cannot increase the supply of real goods. It merely brings about a rearrangement. It diverts capital investment away from the course prescribed by the state of economic wealth and market conditions. It causes production to pursue paths which it would not follow unless the economy were to acquire an increase in material goods. As a result, the upswing lacks a solid base. It is not real prosperity. It is illusory prosperity. It did not develop from an increase in economic wealth. Rather, it arose because the credit expansion created the illusion of such an increase. Sooner or later it must become apparent that this economic situation is built on sand.”[i]

What is more, by increasing credit supply in excess of production gains central banks drive the economies in ever higher levels of debt in relation to income. Such a constellation, in turn, is unsustainable and is most likely to end in a catastrophe — which might go well beyond a mere cyclical slowdown of the economy.

The ability to sustain increasing levels of credit rests upon a vibrant economy, providing incentives for borrowers to take up loans and lenders to keep extending credit. At some point, however, a rising debt level might require too many resources to sustain the level of indebtedness — in terms of meeting interest payments, monitoring credit ratings, chasing delinquent borrowers and writing off bad loans — that it slows overall economic performance. In any case, a high-debt situation becomes unsustainable when the rate of economic growth falls beneath the prevailing rate of interest on money owed.

As Robert Prechter, Jr. points out in Conquer the Crash (John Wiley & Sons, 2002, p. 91), when the burden becomes too great for the economy to support and the trend reverses, reductions in lending, spending, and production make it increasingly hard for debtors to pay off debts. Defaults rise. Default and fear of default exacerbate the situation. A downward spiral begins, feeding on pessimism just as the previous boom fed on optimism. “The resulting cascade of debt liquidation is a deflationary crash,” Prechter writes. “Debts are retired by paying them off, ‘restructuring’, or default. In the first case, no value is lost; in the second, some value; in the third, all value. In desperately trying to raise cash to pay off loans, borrowers bring all kinds of assets to market, including stocks, bonds, commodities and real estate, causing their prices to plummet. The process ends only after the supply of credit falls to a level at which it is collateralized acceptably to the surviving creditors.”

If central banks want to resist the immediate unfolding of an inevitable adjustment of the economy to sustainable debt levels they will have to respond to a weakening in output and employment by cutting borrowing costs further. From the point of mainstream economics, such a policy is usually seen as being a “good policy,” especially in periods of economic downturns, consumer price inflation — monetary policies’ target variable — tends to slow down, recommending an “easier” monetary policy.

As central banks want to escape the disaster they create, they will bring down (real) interest rates over time, whereas economies’ debt levels relative to income rise over time. It doesn’t take much to express concern that such a development will lead towards crisis: “The appearance of periodically recurring economic crises is the necessary consequence of repeatedly renewed attempts to reduce the ‘natural’ rates of interest on the market by means of banking policy. The crises will never disappear so long as men have not learned to avoid such pump-priming, because an artificially stimulated boom must inevitably lead to crisis and depression.”[ii]

A period of depression and deflation — which would be a direct consequence of the need to bring about a new equilibrium between debt levels, incomes and prices — would presumably be rather short-lived and quickly followed by inflation. If the crisis unfolds, translating into real income losses and price declines for many goods and services, public calls for a monetary policy “reflating” the economy can be expected to gain momentum. Under today’s government controlled paper money standard, it is hard to see that central banks would be in a position to withstand such demands.

What is more, a broad scale economic crisis as a result of a credit expansion and inflation policy in the past would almost certainly lead to a new wave of government intervention, posing a threat to the idea of a free market oriented societal order. The crisis will be attributed to the failure of the capitalist system rather than the failure of a government controlled monetary system. That said, today’s short-sighted monetary policy runs the risk of not only destroying the value of the currency but also poses a serious threat to the free market society.

[i] Mises, L. von (1931), “The Causes of the Economics Crisis: An Address,” On the Manipulation of Money and Credit, Ludwig von Mises Institute (2002), Auburn, pp. 188.

[ii] Ibid, p. 190.