In a recent column titled, “Capitalism, Socialism, and Unfreedom,” Paul Krugman lambasted libertarians for equating “freedom” with minimal government. He ridiculed the recently updated Cato index that ranks the 50 U.S. states according to their “freedom” defined in this fashion. Because he lives in New York state—which came in dead last in the Cato ranking—Krugman sarcastically asked a “comrade commissar” in his piece for permission to talk, and in his tweet promoting the column, Krugman said he was writing “from the socialist hellhole of Manhattan.” Besides mocking the (apparent) libertarian claim that New York state was somehow dangerously low in freedom, Krugman’s substantive point was that Americans value other things besides freedom from government intervention. For example, workers in New York state might enjoy the relatively strong unions and Medicaid coverage. Yet as I’ll point out, Krugman’s column is riddled with problems — even his jokes blow up in his face.

Krugman Is “Free” From Self-Awareness

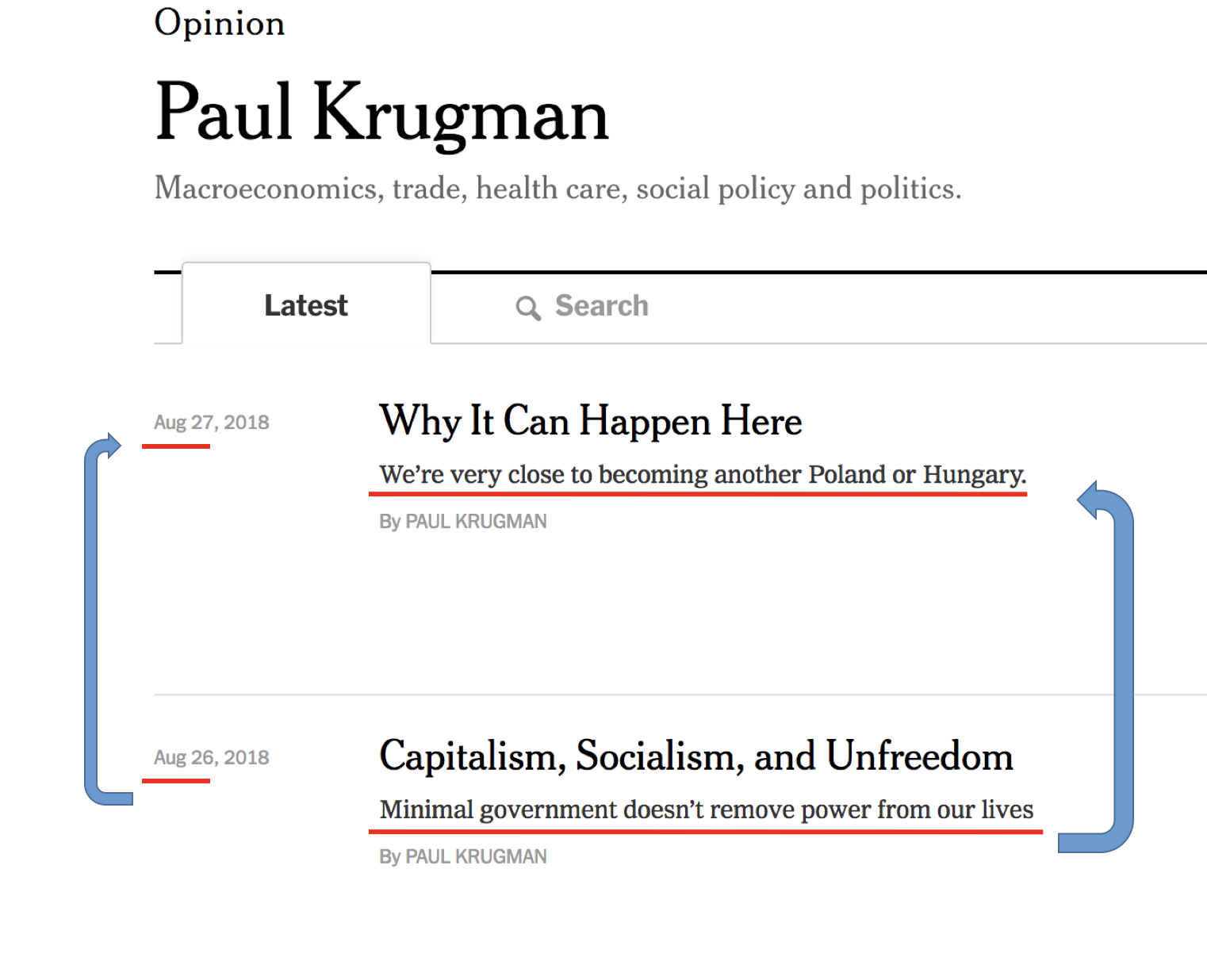

Before diving into the meat of the dispute, let me note something hilarious: Literally the day after Krugman mocks the Cato Institute for ranking U.S. states according to their freedom—such that the state in last place, New York, must be a “socialist hellhole” ha ha—Krugman wrote a column warning his readers that freedom was on the verge of disappearing in America:

As you can see in the screenshot above of Krugman’s archive, on Aug. 26 he pooh-poohed the libertarian warnings about Big Government, and then on Aug. 27 Krugman was warning about autocracy coming in the back door.

What makes Krugman’s 24-hour turnabout even more hilarious is that his Aug. 27 piece relies on alleged examples of Republicans in state governments violating democratic principles. So to sum up: Krugman says the Cato Institute is a bunch of paranoid nutjobs for arguing that New York state has the lowest freedom in the country, but Krugman is allowed to argue that the Republicans in (say) North Carolina are implementing our version of European fascism.

Having Fun With Statistics

In order to show just how (supposedly) silly the Cato study is, Krugman produces a scatter plot pitting the Cato score of a state’s “freedom” against that state’s infant mortality rate. He displays his chart with the following commentary:

The other day I had some fun with the Cato Institute index of economic freedom across states, which finds Florida the freest and New York the least free. (Is it OK for me to write this, comrade commissar?) As I pointed out, freedom Cato-style seems to be associated with, among other things, high infant mortality. Live free and die! (New Hampshire is just behind Florida.)

Before pointing out the problems with it, let’s make sure we understand Krugman’s ostensible point: In the x-axis above, we have a state’s Cato freedom score. (The higher the number, the more freedom.) The y-axis shows the infant mortality rate; the higher the score, the more infants who die. Although he doesn’t mention it in the column, if you follow the link you’ll see Krugman explain that the size of the dot is proportional to a state’s population; that’s why California is so big.

So Krugman is arguing that there is a positive correlation between these two variables, meaning that as you increase a state’s freedom (as Cato measures it), you tend to get a higher infant mortality. Thus, Krugman thinks he has shown just how silly this measure is, and why serious analysts shouldn’t be so simple-minded in focusing on libertarian objectives.

There are several problems with Krugman’s (tongue-in-cheek) analysis. First, notice the rhetorical sleight-of-hand that I put in bold in the quotation above: Krugman tweaks New Hampshire’s “Live Free Or Die” motto, to say “Live Free AND Die,” and then adds, “New Hampshire is just behind Florida.”

But hang on a second. New Hampshire is just behind Florida in its ranking of freedom; that’s why New Hampshire is almost as far to the right as Florida is. (In other words, New Hampshire is ranked #2 in the Cato list, while Florida is #1.)

Yet ironically, as Krugman’s own chart shows, New Hampshire has just about the lowest infant mortality of the 50 states. (This CDC ranking says in 2016 New Hampshire’s infant mortality was the second-lowest in the country, behind only Vermont.)

Thus, Krugman’s joke doesn’t make any sense. The state whose motto he is mocking does indeed live up to its reputation of freedom; it is ranked #2 according to Cato’s measure. Yet it also has the second-lowest rate of infant mortality too. Yet someone reading Krugman’s column and seeing “New Hampshire is just behind Florida,” in conjunction with Krugman’s joke, might have assumed Krugman meant that New Hampshire had a bad mortality rate. (After all, it doesn’t make sense for Krugman to be pointing out New Hampshire on the chart if it completely violated his “point.”)

Stepping back, even the scatter plot as a whole, doesn’t really accomplish what Krugman wants. Visually, he is seeing what he wants to see: Krugman thinks it’s clear (especially if you read his tweet about it) that the best-fit line would be upward sloping in the chart. Yet that is largely because of New York and California. If you exclude them from the analysis, the remaining cloud of states looks like it might exhibit a downward slope.

We don’t need to speculate. I asked Jason Sorens, one of the co-authors on the Cato study, to crunch the numbers. He did it a few different ways. First, he included all of the states, and found that the correlation (specifically, the Pearson coefficient) between infant mortality and “freedom” was 0.20. (Keep in mind that a correlation of 1.00 occurs when two variables are perfectly positively linearly correlated, while 0.00 means they are not at all linearly correlated.) Even here, the correlation wasn’t statistically significant; there was too much variability / not enough data points to be confident in the observed relationship.

Sorens also checked my intuition: If you remove NY and CA from the data, then the correlation between infant mortality and “freedom” drops to 0.07 (meaning no real relationship one way or the other). Finally, Sorens did what he thought was the most sensible adjustment: He kept the data for all 50 states, but he controlled for a state being in the South, and for per capita income. Doing that, the correlation between infant mortality and “freedom” drops to 0.03.

Obviously, what is happening here is that there are omitted variables. It’s not that freedom per se “causes” a state to have a higher infant mortality rate. For whatever reason, in recent years, states with relatively more freedom also happen to have higher infant mortality rates, though the correlation is very weak.

Calling Krugman’s Bluff

Now I imagine Krugman would say, “Exactly! That’s my point! You libertarians narrowly look at the world in terms of freedom—as you define it, meaning freedom from government meddling in your personal life and business — but there’s more to life than Ayn Rand. If a Big Government uses its regulations and tax receipts to, say, guarantee health care and good schools, then we would expect to see high quality of life go hand-in-hand with low scores of economic freedom.”

Yet if this is the general argument Krugman would pursue, he runs into a problem. Even though he can find particular correlations that are amusing—such as looking at the most recent infant mortality data just among the 50 U.S. states—then sure, it looks like focusing narrowly on “freedom” is goofy.

But places like the Fraser Institute and Heritage Foundation have produced global rankings of countries, and there are dozens if not hundreds of empirical studies showing that “economic freedom” at the national level is indeed statistically associated with all sorts of desirable social indicators. (To avoid confusion, the Cato measure of “freedom” is broad, whereas the Fraser and Heritage rankings focus specifically on economic freedom.)

Back in 2009, Lawrence McQuillan and I did a study for Pacific Research Institute, titled “The Sizzle of Economic Freedom,” that summarized some of these findings. For example, using samples covering several continents and decades of observations (the details differ from study to study), we described studies that showed economic freedom being associated with higher personal income, lower unemployment rates, faster economic growth, more business startups, and more macroeconomic stability.

This was perhaps expected. But we also showed that economic freedom was positively associated with lower levels of inequality, a cleaner environment, lower childhood mortality rates, higher life expectancies at birth, and higher measures of political freedom. (For more research along these lines, check out Fraser’s page dedicated to its freedom index.)

Which States Do Workers Prefer? Voting With Their Feet

To drive home his main point, Krugman contrasts the different forms of power/freedom that citizens in New York face, compared to Florida. (Remember that New York scored lowest on Cato’s ranking, while Florida scored the highest.)

But seriously, do the real differences between New York and Florida make New Yorkers less free? New York is a highly unionized state...Does this make NY workers less free, or does it empower them in the face of corporate power?

Also, New York has expanded Medicaid and tried to make the ACA exchanges work, so that only 8 percent of nonelderly adults are uninsured, compared with 18 percent in Florida. Are New Yorkers chafing under the heavy hand of health law, or do they feel freer knowing that they’re at much less risk of being ruined by medical emergency – or cast into the abyss if they lose their job?

If you’re a highly paid professional, it probably doesn’t make much difference. But my guess is that most workers feel at least somewhat freer in New York than they do in FL. [Krugman, bold added.]

Well, I guess it would be hard to truly get inside everybody’s head, but here’s a simple test to see which set of policies people prefer: Look at where they live. Namely, if we tend to see people moving out of states with high taxes and excessive regulations, and into states with low taxes and light regulations, then that’s pretty good evidence that Krugman is dead wrong.

Fortunately, we have a convenient map of net domestic migration that we can grab from this Business Insider article:

What this map shows is the net domestic migration into or out of a state, as a fraction of the state’s population. So to be clear, these figures exclude immigration from abroad, and just keep track of how many people “internally” moved into or out of a state, from July 1, 2016 to July 1, 2017. Positive numbers mean more people moved into a state, and negative numbers mean more people moved out, on net.

If you compare this map with Krugman’s scatter plot, you can see a general pattern: the states with low levels of economic freedom (i.e. the ones on the left in Krugman’s plot) tend to be losing population, i.e. have negative numbers in the map. For example, California lost 3.5 out of 1,000 of its population if we just consider domestic migration, while New York lost a whopping 9.6 residents out of 1,000.

In contrast, the states with high levels of economic freedom are gaining people. For example, Florida gained 7.8 per 1000 residents, and New Hampshire gained 3.5.

You can try it the other way, too. For example, the Business Insider map shows that Wyoming lost 14.7 out of 1,000 of its population (in terms of internal migration). The Cato interactive map indicates that Wyoming was ranked #38 in economic freedom (i.e. toward the bottom). In contrast, Arizona gained 9.1 per 1000 population (in this measure), and the Cato ranking says it has a freedom ranking of #9 in the country.

Now to be sure, there are some problems with my approach. Most serious, I believe that the way these calculations work, border states like California (but also Texas) get “dinged” because they have large flows of foreign immigrants coming in, who then eventually might move to internal states. Even so, that type of issue doesn’t explain away the clear pattern that holds even among the internal states.

More generally, I recognize that there are other factors at play, besides economic freedom. For example, distant places like Hawaii and Alaska might have a net outflow simply because many people who are born in those states end up moving away at some point, for reasons that aren’t really due to “the low degree of economic freedom in my hometown.”

Despite these caveats, I think the aggregate flow of population among the 50 states is a much better indicator of how people subjectively evaluate the pros and cons of economic freedom. And it seems as if they tend to flock to the states that do better on Cato’s ranking. People do indeed seem to be fleeing the “socialist hellhole” where Krugman resides.

Indeed, this isn’t just my theory. I once read a Nobel economist who said:

But all too many blue states end up, in practice, letting zoning be a tool, not of good land use, but of NIMBYism, preventing the construction of new housing.

In fact, liberal (in the non-political sense) land use policy is probably the secret behind Texas economic growth: the state doesn’t offer high wages, but it does offer cheap housing even in huge metro areas.

Who was this mystery economist, who argues that Texas’ minimal zoning regulations explain its strong economy? Long-time readers know that when I’m being coy, it’s because I’m quoting Paul Krugman to make my point.

Conclusion

Paul Krugman tried to mock the idea that a ranking of U.S. states by economic freedom was a useful exercise. He put words in the authors’ mouths by sarcastically saying New York must be a “socialist hellhole”—even though literally the next day, Krugman pointed to the behavior of a few state legislatures to argue that American democracy was on the verge of disappearing.

More substantively, Krugman argued that “freedom” was only one of several things important to Americans, and that a strong government could provide other desirable goods—such as protection from employers and health insurance. Yet empirical studies show that over long stretches and across multiple countries, economic freedom really is positively associated with all sorts of measures, including not just income and GDP growth, but also a cleaner environment, lower childhood mortality, and measures of political freedom.

Finally, even if we restrict our attention to the U.S., we see that Americans tend to move out of low-freedom states and into high-freedom states. Believe it or not, Prof. Krugman, most people don’t share your enthusiasm for Big Government.