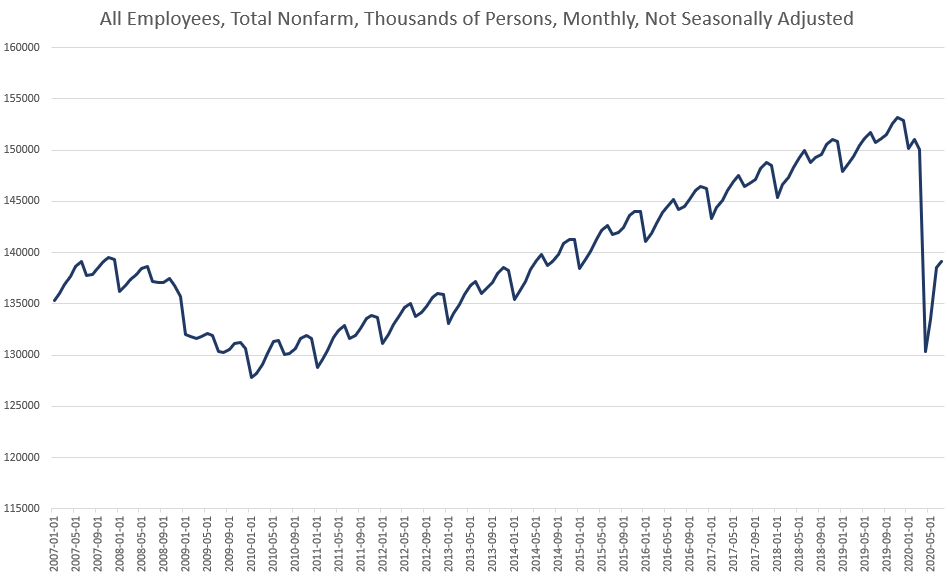

Growth in total employment slowed in July, following two months of big gains in employment, during May and June. But it all comes after the US economy shed more than 19 million jobs during March and April.

In July, the US added 591,000 payroll jobs, with total employment rising to 139.1 million. This is a sizable slowing from June, when more than 5 million jobs were added. At its most recent peak in November 2019, more than a 153 million Americans were employed. From November to July, the US is down 14 million jobs, or 6.7 percent of the US’s working age population.

In other words, the US remains well below peak employment, and at three months since enormous job losses began to mount, it remains unclear if the jobs recovery will require several years, as was the case after the 2008 financial crisis.

As of July, total employment is at 90 percent of peak levels, which is below anything we saw during the previous four recessions. At its nadir, employment fell to 91 percent of the peak during the 2007–09 recession (the Great Recession). But from that point, four years went by before employment returned to its former peak level.

Many commentators on the current crisis have insisted that the US will experience a rapid “V-shaped” jobs recovery. This result, however, is far from guaranteed, especially if the world’s governments revert to mandating forced “lockdowns” and business closures again this summer or later this year.

The graph shows total employment indexed to the previous peak. For example, the black line shows the number of months since the previous jobs peak (November 2019), during which jobs remain below peak levels. Similarly, the brown line shows the number of months after the June 2007 jobs peak that total employment remained below peak levels. Recent jobs recoveries have taken significantly longer than was the case during the 1980s and 1990s.

The unemployment rate remains at recessionary levels as well. July’s unemployment rate was 10.5 percent, slightly below the peak unemployment rate during the Great Recession, when it was 10.6 percent. In any case, of course, this is a high unemployment rate.

So, is there any sign yet that the jobs recovery will soon come roaring back?

Not really.

The Labor Department also released new data on initial unemployment claims, and new claims data shows only very slow progress being made.

As of the week of August 1, 984,000 workers filed for initial unemployment benefits. This is a decrease from the previous week’s total of 1.2 million, and it is well down from the the 6.2 million newly unemployed that filed for benefits the week of April 4. However, at nearly 1 million, the number of newly unemployed remained higher than during any week recorded during the Great Recession.

Moreover, these are just newly unemployed. Continued unemployment claims as of the week of July 25 still showed that more than 15.8 million Americans were receiving unemployment benefits. This is more than double than what we saw at the peak of the Great Recession, when continuing claims hit 6.4 million.

Looking at the unemployment claims and payroll data combined, it is extremely likely the US now has at least 15 million unemployed workers, and there is no guarantee that most of these can look forward to a quick rehire so long as there remains the looming threat of government-forced shutdowns. Thanks to threatened shutdowns, regime uncertainty remains immense for employers, which is likely to reduce the demand for employees or business expansion.

What Can Be Done?

What could be done to help the situation? The first necessary step would be to end the threat of forced government shutdowns and forced changes in business capacity. As it is, the current spate of executive orders being issued by the one-man rule-by-decree regimes in place in most US states amounts to a huge expansion of the regulatory state. Business shutdowns and new requirements on building use and building capacity impose enormous financial and regulatory burdens on business owners. Naturally, hiring suffers as a result. If policymakers wanted to actually do something about unemployment—as well as the enormous public health burden that results, in the form of suicides and other threats to health—they would immediately announce that the threat of business closures has passed. Until this happens, expect hiring to remain lackluster.

This isn’t to say that businesses would not need to adapt to a public that—even in the absence of government mandates—is likely to reduce spending on certain goods and services that are now less attractive in light of fears over the covid-19 disease. However, so long as governments continue to hand the threat of shutdowns and additional regulations over the heads of employers, this will continue to hamstring businesses’ ability to adapt to new realities and will greatly hamper employment.

A second important step would be to reduce the overall regulatory burden. This would include regulations that predate the current round of job-killing mandates. These include rules on hiring such as minimum wage laws, licensing regulations, and other measures designed to limit hiring and employment in the alleged pursuit of higher quality or “higher wages.” The real result from all these measures is that employment is outlawed for wide swaths of the population and entrepreneurs are prohibited from expanding their own services or from hiring others.

The need to reduce barriers to employment is greater now more than ever. In July, more than 32 percent of Americans missed their housing payments. Evictions are mounting. More Americans, due to income losses, are unable to pay the rent. Politicians—in the the thrall of well-paid and out-of-touch health bureaucrats—have decided this is no big deal and refuse to take the necessary steps to allow entrepreneurs and employers to usher in a jobs recovery. So long as these “public health” officials dictate economic policy, more and more Americans will become unemployed and destitute. Many will become homeless. The effects of the jobs implosion are just beginning to be felt.