Five years ago, in November 2005, the Federal Reserve announced that it would no longer be tracking the aggregate money supply. It issued a terse, cryptic 143-word press release entitled the “Discontinuance of M3.” M3 was the broadest member of the big 4 of monetary aggregates published by the Fed — M0, M1, M2, and M3 that the Fed had compiled monthly since 1959.

John Williams of Shadowstats noted the oddity of the announcement, opining that M3 was probably the most important statistic produced by the Fed and the best leading indicator of economic activity and inflation. The Fed’s lack of interest in the components of M3 can be directly linked to its inability to foresee the 2008 collapse of the financial system.

The American fiat, credit-money system starts with the Fed-supplied monetary base and pyramids upward through commercial banks, investment banks, offshore banks, nonbanks, and other credit providing entities. The “Ms” provide the Fed’s calculation of the money levels at different tiers of the credit pyramid to the markets.

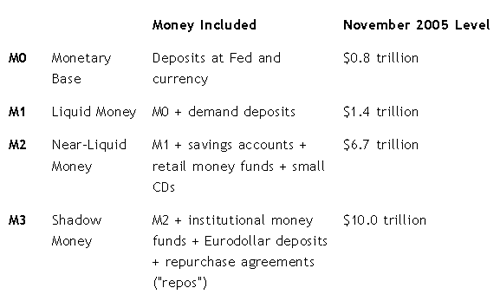

Here is a synopsis of each of these metrics and where they stood in November 2005:

With this decision, $3.3 trillion (the difference between M3 and M2) effectively disappeared off the Federal Reserve and the market’s radar screen. The Fed also stated that it would cease publication of Eurodollar, Repo, and institutional time-deposit data, though some intrepid analysts reconstruct this data by taking snapshots of the Fed’s balance sheet.

The two now-missing components of M3, Eurodollars and repos, are the “Wild West” of the money supply. Eurodollars are US dollar deposits held by non-US banks in places like London, the Bahamas, the Cayman Islands, and Iceland (while it lasted). They are not subject to US regulations and therefore can be levered up, free of reserve or reporting requirements. Eurodollar banks have been known to operate at 50:1 leverage ratios.

Repos are short-term, often overnight, loans made to financial companies that are collateralized by securities in the possession of the borrowing company. They are a critical financing source for investment-bank trading and lending businesses. In the early years of the repo market, the primary collateral was US Treasury Securities. Today, the primary collateral consists in complex derivative securities, such as asset-backed securities (RMBS/CMBS/ABS), collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), and collateralized derivative obligations (CDOs). Repos are also not subject to reserve or reporting requirements, leading to high leverage ratios in investment banks (e.g., Lehman Brothers at 30:1).

“If the Fed had been tracking repos in 2007–2008, what they would have seen was the unfolding of the financial crisis one full year before it went critical.”M3 was a highly imperfect statistic in that it did not capture the full extent of the leverage. On Eurodollars, M3 only included Eurodollar deposits held by American bank holding companies. Given that the vast majority of Eurodollar activity takes place overseas through foreign banks, this is analogous to monitoring the global oil supply by sampling production data out of Alaska. On repos, the Fed only tracked repos beween itself and its primary dealers. According to Yale economists Gary Gorton and Andrew Metrick, there are no official statistics on the overall size of the repo market. They estimate that the Fed’s balance sheet could account for only $4.5 trillion of the overall $12 trillion repo market in 2008, making it even larger than the $10 trillion in assets in the US banking system.1 In other words, the repo market is bigger than the US banking system, but is unaccounted for by the Fed.

If the Fed had been tracking repos in 2007–2008, what they would have seen was the unfolding of the financial crisis one full year before it went critical. From Q3 2007 through Q2 2008, the repo market was starting to seize with lenders starting to demand higher and higher haircuts on collateral. In early Q1 2008, Shadowstats estimates that the rate of M3 growth started to decline rapidly as repo activity cooled. Then in September 2008, the repo market decided that it was unwise to lend additional funds to Lehman Brothers and the rest is history.

Let us now return to the curious press release of November 10, 2005. The Fed explained its decision to stop collecting and publishing the data as follows:

On March 23, 2006, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System will cease publication of the M3 monetary aggregate. … M3 does not appear to convey any additional information about economic activity that is not already embodied in M2 and has not played a role in the monetary policy process for many years. Consequently, the Board judged that the costs of collecting the underlying data and publishing M3 outweigh the benefits.

The Fed’s statement boils down to three reasons for the discontinuance:

- M3 does not provide additional information. This statement would only be true to an economist who believed that the aggregate money supply was unimportant.

- M3 does not play a role in monetary policy. As Bernanke has now shown through various money-printing initiatives — QE1, QE2, TARP, TALF, etc. — he is truly unconcerned with the aggregate money supply and therefore it does not play a role in monetary policy.

- M3 is too expensive to collect. The Fed estimated that it spent $500,000 per year to collect the data and banks spent $1,000,000 in aggregate to provide the data. This expense is not even a rounding error against the $21.5 billion in (paper) profit that the Fed reported in 2005.

November 2005 was the interregnum between the long tenure of Alan Greenspan and newly appointed Chairman Bernanke. Most of the media coverage of the Fed at the time was a celebration of the Maestro and his wise stewardship of the economy. Thus, there was almost no reporting or domestic criticism of the discontinuance of M3. There were many concerns expressed by sophisticated fund managers, analysts, and foreign investors (central banks). There was also one meek and humorous attempt by Congress to inquire into the M3 decision. Here is a wonderful snippet of Bernanke doublespeak from November 15, 2005:

Senator Bunning: The findings of the M3 report provide pertinent information to the public — from economists to investors and to industries which all use M3 report findings for economic forecasting, investing and business decisions. … Will you work to reverse this policy and commit to keeping the M3 report and its findings available and open to the public? What is the rationale and reasoning behind the Federal Reserve decision to keep the M3 information from the public?

Bernanke: The Federal Reserve will not withhold the M3 data from the public; rather, it will no longer collect and assemble that information.

How comforting.

- 1See “Haircuts” in the Federal Bank of St. Louis Review, Nov/Dec 2010, p. 57.