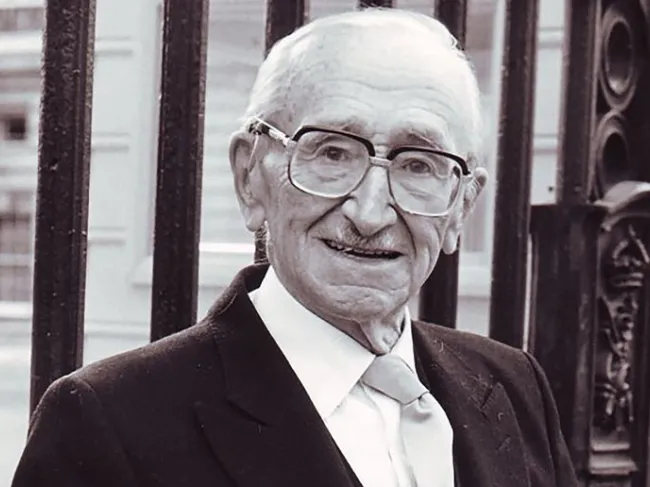

The grant of a 1974 Nobel Prize in Economic Science to the great Austrian free-market economist Dr. Friedrich A. von Hayek comes as a welcome and blockbuster surprise to his free-market admirers in this country and throughout the world. For since the death last year of Hayek’s distinguished mentor, Ludwig von Mises, the 75-year-old Hayek ranks as the world’s most eminent free-market economist and advocate of the free society.

The Nobel award comes as a surprise on two counts. Not only because all the previous Nobel Prizes in economics have gone to left-liberals and opponents of the free market, but also because they have gone uniformly to economists who have transformed the discipline into a supposed “science” filled with mathematical jargon and unrealistic “models” which are then used to criticize the free-enterprise system and to attempt to plan the economy by the central government.

F.A. Hayek is not only the leading free-market economist; he has also led the way in attacking the mathematical models and the planning pretensions of the would-be “scientists,” and in integrating economics into a wider libertarian social philosophy. Both concepts have so far been anathema to the Nobel establishment.

We can only speculate on the motivations of the Nobel committee in this welcome, if overdue, tribute to Friedrich von Hayek. Perhaps one reason is the evident and galloping breakdown of orthodox Keynesian “macroeconomics,” which leads even the most hidebound economists to at least consider alternative theories and solutions. Perhaps another reason was a desire to grant a co–Nobel Prize to the notorious left-wing socialist Dr. Gunnar Myrdal, and granting one to Hayek out of a recognized need for political “balance.” Thus, in granting prizes to these two polar opposites, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences cited both Hayek and Myrdal “for their pioneering work in the theory of money and economic fluctuations and for their pioneering analysis of the interdependence of economic, social and institutional phenomena.”

At any rate, regardless of the motivations of the Nobel committee, we can only hail their richly deserved tribute to the towering contributions and achievements of Friedrich von Hayek. Hayek’s first monumental contribution to economics was his development of the “Austrian” theory of the business cycle, based on the pioneering outline of Mises. Appearing in the late 1920s, on the basis of which Mises and Hayek were among the very few economists in the world to predict the 1929 Depression, Hayek’s two great works on the business cycle appeared in English as Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle (1933) and the more technical Prices and Production (1931).

During the early 1930s, when Hayek had immigrated from Austria to teach at the London School of Economics, the Mises-Hayek theory of the business cycle began to be adopted widely in England and even in the United States as an explanation of the Great Depression; unfortunately, this Austrian theory was swept aside in the jubilation of the Keynesian revolution (1936) without being even considered, much less refuted by the statist Keynesians. Now that Keynesianism is crumbling both theoretically and empirically, the world of economics should be ripe to consider the Austrian theory seriously again, for the first time in forty years.

Briefly, the importance of the Hayek theory of the business cycle is that it puts the blame for the boom-bust cycle squarely on the shoulders of the government and its controlled banking system, and, for the first time since the classical economists of the 19th century, completely absolves the free-enterprise economy from the blame. When the government and its central bank encourages the expansion of bank credit, it not only causes price inflation, but it also causes increasing malinvestments, specifically unsound investments in capital goods and underproduction of consumer goods.

Hence, the government-induced inflationary boom not only injures consumers by raising prices and the cost of living but also distorts production and creates unsound investments. The government is then faced repeatedly with two basic choices: either stop its monetary and bank-credit inflation, which then will necessarily be followed by a recession, which serves to liquidate the unsound investments and return to a genuinely free-market structure of investment and production — or continue inflating until a runaway inflation totally destroys the currency and brings about social and economic chaos.

The relevance of the Hayek theory to the present day should be glaringly obvious, as any hint of recession causes the government to panic and turn on the inflationary taps once again. The point is that, given any inflationary boom, a recession is painful but necessary, in order to return the economy to a sound state.

The political prescription that flows from the Hayekian theory is, of course, the diametric opposite of the Keynesian: stop the artificial inflationary boom, and allow the recession to proceed as fast as possible with its work of readjustment. Postponement and government attempts to stop or interfere with the recession process will only drag out and intensify the agony and lead to our current and probably future turmoil of inflation combined with lengthy recession and depression. The Mises-Hayek analysis is not only the only cogent theory of the business cycle; it is the only comprehensive free-market answer to the Keynesian morass of government planning and “fine tuning” that we are suffering from today.

But F.A. Hayek did not stop with this monumental contribution to economics. In the 1940s he widened his approach to the entire area of political economy. In his best-selling Road to Serfdom (1944) he challenged the prosocialist and pro-Communist intellectual climate of the day, showing how socialist planning must inevitably lead to totalitarianism, and demonstrating examples in the way in which the socialistic Weimar Republic paved the way for Hitler. He also showed how the “worst always get to the top” in a statist society.

In his brilliant series of essays in Individualism and Economic Order (1948), Hayek pioneered in demonstrating how socialism cannot rationally calculate because it lacks a free-market pricing system, particularly since the free market is uniquely equipped to transmit information from every individual to all other individuals. Lacking a genuine price system, socialism is necessarily devoid of such crucial information.

Furthermore, in the same work, Hayek brilliantly dissected the unrealistic orthodox model of “perfect competition,” demonstrating that the real world of free competition is far superior to the absurd call for “perfection” by trust-busting lawyers and economists. As a corollary, Hayek in this work began a devastating series of attacks on the mathematical economists’ model of “general equilibrium,” showing how absurd and unrealistic such a criterion was with which to beat free enterprise over the head.

In 1952, Hayek published his superb Counter-Revolution of Science, which remains the best attack on the pretensions of would-be planners to run all of our lives in the name of “reason” and “science.” Two years later, in the very readable Capitalism and the Historians, Hayek contributed to and edited a series of essays that showed conclusively that the Industrial Revolution in England, spurred by a roughly free-market economy, enormously improved rather than crippled the standard of living of the average consumer and worker in England. In this way, Hayek led the way in shattering one of the most widespread socialist myths about the Industrial Revolution.

Finally, in his Constitution of Liberty (1960), Studies in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics (1967), and Law, Legislation, and Liberty (1973), Hayek, among other notable contributions, upheld the forgotten ideal of the rule of law rather than men, and emphasized the unique value of the free market and the free society in creating a “spontaneous order” that can only emerge from freedom. As merely one of his achievements, his much anthologized article, “The Non-Sequitur of the ‘Dependence Effect’,” demolished J.K. Galbraith’s The Affluent Society in pointing out that there is nothing wrong with individuals learning and absorbing values and consumer desires from one another. And in his scintillating essay, “The Intellectuals and Socialism,” F.A. Hayek set forth the proper strategy for libertarians to follow: the importance of having the courage to follow the socialists in being consistent, in refusing to surrender to the short-run dictates of compromise and expediency; only in that way will we be able to roll back and defeat the collectivist tide.

We could go on and on. But enough has been said here to point to the great scope, erudition, and richness of F.A. Hayek’s contributions to economics and to political philosophy. Like his great mentor, Ludwig von Mises, F.A. Hayek has persisted with high courage in opposing the socialism and statism of our time. But not only has he unswervingly opposed the current fashions of Keynesianism, inflation, and socialism; he has — with nobility, courtesy, and great erudition — pursued his researches to provide us with the alternative concepts of the free economy and the free society.

F.A. Hayek richly deserves not only the Nobel Prize but any honors we can bestow upon him. But the greatest tribute we can make, to Hayek and to Mises, is to dedicate ourselves to rolling back the statist tide and proceeding onward to a society of freedom.

This article was originally published in Human Events, November 16, 1974, p. 18. It was reprinted in Libertarian Forum, Vol. 6, No. 10.![]()