It seems that many residents of the West Coast and the Northeast are leaving those regions behind.

In March, for example, the Sacramento Bee reported that California “exports its poor to Texas ... while wealthier people move in.” Former Californians report that a lackluster job market, a high cost of living, and high taxes are pushing them out.

This week, Chicago Magazine reported on Chicago’s highly publicized diaspora. One interviewee reported the crime, high cost of living, and taxes drove him out of Illinois and across the state line to northern Indiana. “I couldn’t have this size house in Illinois,” he said.

Last week, Bloomberg reported that state-to-state mobility is strong with increasing numbers of workers moving to “rapidly growing regions where employment is plentiful.”

The United States has long been notable for the frequency with which its residents move around. This isn’t always without social and psychic costs to those who move, and their communities.

But, the ease with which workers and families can pick up and move across state lines provides many with the option of moving to a totally new geographic and legal environment where the burdens of taxes and the cost of living may vary greatly. Best of all, unlike Europe, there is no language barrier that comes with moving across the continent to find a new job.

If one can take advantage of the amenities of other states with relative ease, then residents are more likely to leave behind their current situation for what they perceive to be better digs.

Thus, according to the 2015 American Community Survey numbers released late last year — the most recent number available — 7.5 million Americans lived in another state just one year earlier — and thus decided that the time had come to move from their home states.

But, of course, those who moved were not evenly distributed, and there are some big differences by region.

When we look at the net number of residents moving in from other states, we find that the destination for most of these 7.5 million migrants was states in the South and in the West — excluding California:

The map, however, fails to account for just how large was the migration out of certain states, specifically, New York, California, Illinois, and New Jersey. When we ignore foreign migrants and look at just state-to-state flows, we find that more than 191,000 people left New York while more than 129,000 people left California. The top destinations for migrants were Florida, Texas, and North Carolina1 :

These are net numbers, meaning that even when we count new arrivals from other states, these states lost residents.

One objection we might raise here is the fact that the two states fueling the most out-migration have very large populations. How big is the population loss, really, if we look at it in terms of percentages?

It turns out that in many places the loss, relatively speaking, is still quite large:

Even when taking into account population loss proportional to the overall population, Illinois (-1 percent), New York (-0.9 percent), and New Jersey (-0.9 percent) still top the list, with Alaska (-0.8) and Connecticut (-0.7) not far behind. By this measure, California — which was second-worst in the nation in terms of raw numbers — is only the fourteenth biggest loser in terms of the percentage of its population that moved away.

The states with the biggest proportional gains were Delaware (+1.4 percent), North Dakota (+1.4 percent), Nevada (+1.2 percent), Idaho (+0.1 percent), and Arizona (+0.1 percent).

Where did all those Californians go?

According to the survey, 643,000 people living outside California in the US had lived in California one year earlier. In Colorado — the state with the eighth-largest proportional increase, and a popular destination for Californians — 12 percent of the 227,000 people who moved to Colorado during the survey period were from California alone. That is, 29,000 people moved from California to Colorado. The next biggest source of migrants to Colorado was Texas which supplied 11 percent of all new arrivals.

Things look different on the east coast where more new arrivals are from New York.

Although Florida was among the states with top net population growth, a lot of people also moved away from the state during 2015. Many of them moved to North Carolina.

But why are people leaving states like California, New York, and Illinois in such large numbers? Put another way: why are so few choosing to move there?

It could be any number of reasons from taxes to climate and to employment.

But, it’s likely no coincidence that according to the BEA, the most expensive states to live in are Hawaii, New York, New Jersey, and California. All of those states experienced a net loss of residents to other states.

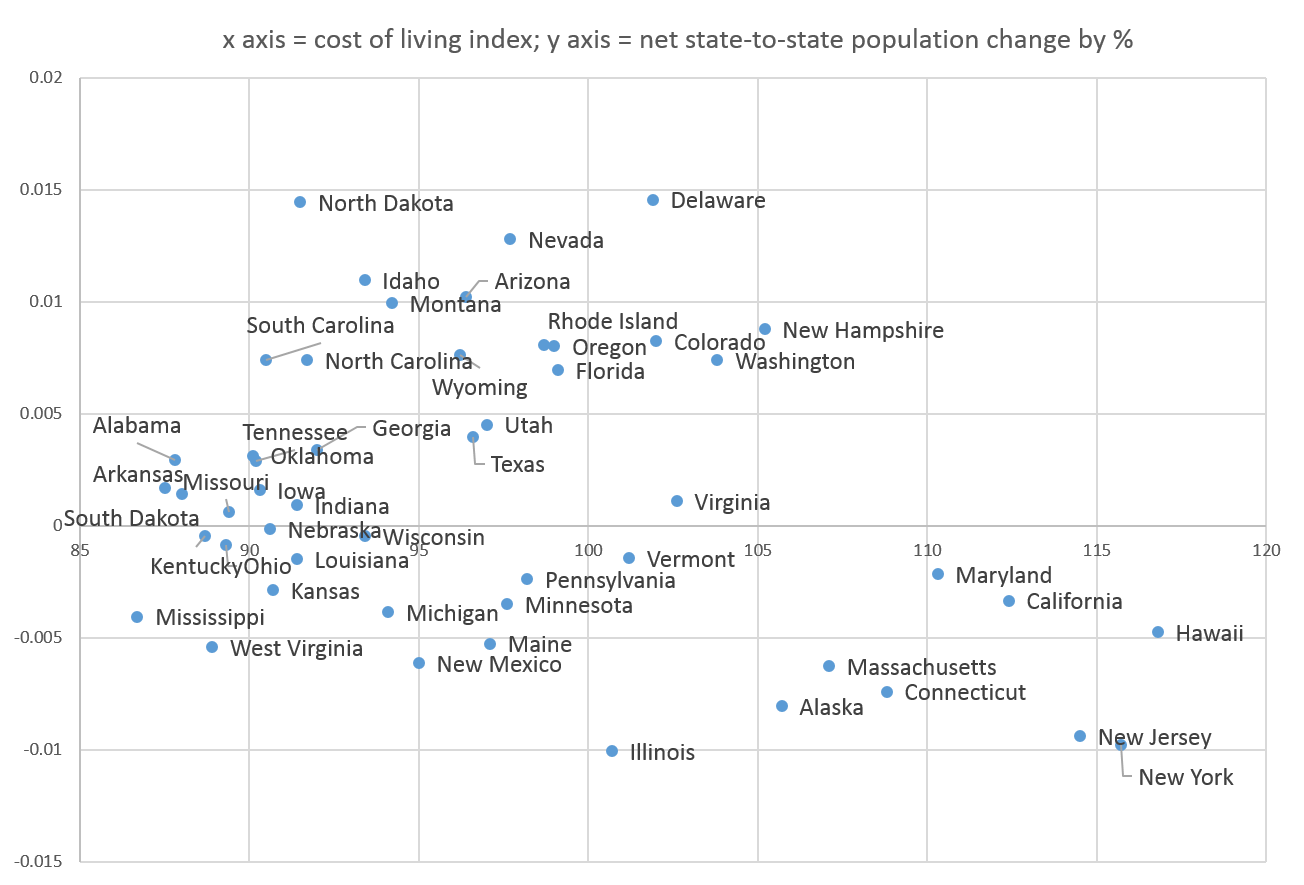

When we employ a basic scatter plot of state-to-state migration with the “Regional Price Parity” measure of the cost of living, we find that above an index of 105, only New Hampshire experienced a rise in new residents from other states:

Nor is it likely a coincidence that, using the Tax Foundation’s measure of tax burden, California, New York, and New Jersey are found among the states with the largest tax burden, and the largest population loss to other states. Eight of the ten states with the highest tax burdens experienced population loss to other states.

On the other hand, states like California, New York, and Illinois can seek comfort in the fact that their populations aren’t really declining in absolute terms thanks to migration from foreign countries. California residents may be fleeing to other states, but those former residents are being replaced by new residents from abroad.

Can this be sustainable over time? It depends on the nature of those moving away and those moving in. If those leaving California and New York are highly productive workers seeking a tax break and lower cost of living, then this could lead to a net drain of wealth-producing people. On the other hand, if those moving to new states are primarily retirees or low productivity workers, then the states they’re leaving may do just fine with new immigrants who may be able to easily replace those who are leaving.

- 1All calculations in this article ignore foreign migrants and focus only on state-to-state flows.