Eurozone banks have fallen dramatically in the stock market despite the results of the stress tests carried out by the ECB, and the EU Banks Index is down 25% on the year despite year-long bullish recommendations from almost every broker. This should not surprise anyone because we have seen in the past that these tests are only a theoretical exercise. Moreover, stress tests’ results are widely challenged, and rightly so, because the exercise starts with the most ridiculous premise in economics: Ceteris Paribus, or “all else remaining equal”, which never happens. Every asset manager knows that risk builds slowly and happens fast.

Disappointing earnings, rising risk in the eurozone as well as in their diversification markets such as emerging economies, weak net income margins and low return on tangible equity are factors that have contributed to the weak performance of European banks. Investors are rightly suspicious about consensus estimates for 2019 with expectations of double-digit EPS growth rates. Those growth rates look impossible in the current macroeconomic scenario.

Eurozone banks have done a good job of strengthening their capital structure, reaching almost a one per cent per annum increase in Tier 1 core capital. The question is whether this improvement is enough.

Two factors weigh on sentiment.

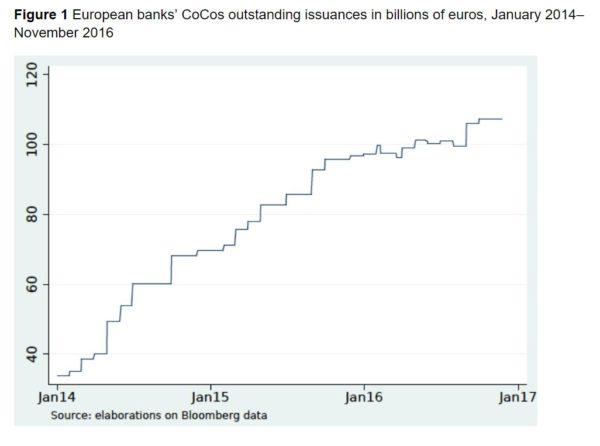

- More than EUR104 billion of risky “hybrid bonds” (CoCos) are included in the calculation of core capital.

- The total volume of Non-Performing Loans across the European Union is still at around EUR 900 billion, well above pre-crisis levels, with a provision ratio of only 50.7%, according to the European Commission. Although the ratio has declined to 4.4%, down by roughly 1 percentage point year-on-year, the absolute figure remains elevated and the provision ratio is too small.

This is what I call the “one trillion euro timebomb.” One trillion euro risk when the MSCI Europe Bank index has a total market capitalization of around EUR 790 billion.

(Source: Bloomberg, Bologna, Miglietta, Segura)

Let us focus on the CoCos, because it is a less commented issue.

The EUR104 billion of CoCos can be a double-edged sword. On one side, they have been one of the favourite instruments to improve core capital rapidly. It was a very popular instrument in recent years to reinforce capital and diversify funding sources. On the other hand, it is a highly risky asset that can create a domino effect on the equity and the other bonds of the entity. Let us face it, the idea that a CoCo can default with no contagion risk to the rest of the capital structure is simply ludicrous.

These CoCos are hybrid bonds. Rating agencies assign them up to a 50% of ‘equity’ component because the investor can lose the entire coupon, as well as part or all the principal if the issuer’s capital ratio falls below 7% or 5%.

These high-risk bonds have been issued widely and with great success in a world in which investors were hungry for some yield in the face of falling interest rates when many assumed the rising strength of banks. It was almost a “no brainer”. Core capital was rising, banks were stronger than ever, and the yields of these Co-Cos ranged between 4 and 7%. Except the risk was much higher.

In 2011, European banks issued 10 billion euros in these products with returns that reached 10%. It seemed a safe business with almost no risk of default.

The policy of central banks and financial repression, once again, led investors to take more risk for lower yields.

By 2017, Eurozone banks had issued more than 70 billion euros with yields that fell to 4%.

From 10% to 4% yield as risks were gradually building, bank stocks were falling and economic data began to disappoint.

These products were extremely popular because few investors thought the banks would have any problem meeting the required 10% Tier 1 core capital figure. The risk of breaching the core capital threshold seemed impossible.

“Impossible” and “no risk” are very dangerous words in any asset class. In hybrid bonds, it is reckless to believe in no risk.

A recent paper (Contagion in the European CoCos market) by professors Pierluigi Bologna, Arianna Miglietta and Anatoli Segura, concludes: “The recapitalisation of the banks as a going concern provided by CoCos cannot be detrimental for the stability of the rest of the market. Should the operational features of CoCos keep on proving destabilising in future stress situations, rethinking their role as bank regulatory capital tools would be necessary”.

Unsurprisingly, CoCos have fallen sharply and created a domino effect that impacts equities as well.

The idea that a bond can default with no threat to the equity or solvency of the issuing bank could have only occurred to central planners with no clue of risk and contagion.

Eurozone banks bounced in late August while forward earnings estimates were falling (see above).

Risks in CoCos are evident. In NPLs, concerns are mounting :

- Weaker earnings from the borrowers due to the slowdown. According to the BIS, the percentage of large zombie companies (those that cannot pay interest expenses with operating profits) has soared to 9% of quoted names.

- The need to accelerate recapitalization to avoid the next crisis will make it less easy to refinance NPLs.

- The impact of the global slowdown in banks that had opted to grow in emerging markets, commodities and public infrastructure financing.

Anyone who believes these two problems will be solved by extending quantitative easing and low rates has learnt nothing from the past years.

What these risks show is that eurozone banks need to implement a much more aggressive recapitalization plan . Capital increases and eliminating cash dividends will likely have to return. Managers do not want to do it because shares are too low according to them. However, waiting for a bounce has proven to be a big mistake. 2018 was the year of the perfect combination to drive banks shares higher: Confidence in the eurozone, the likelihood of rate hikes, improvement of fundamentals and earnings growth. None of it happened. Waiting for things to get better for asset classes is not enough.

Eurozone banks are better than three years ago. They are nowhere close to having solved their challenges.