Since 2008, a key component of Fed policy has been to buy up mortgage-based securities and government debt so as to both prop up asset prices and increase the money supply. Over this time, the Fed has bought nearly $9 trillion in assets, thus augmenting demand and increasing prices for both government bonds and housing assets. Moreover, these purchases were made with newly created money, contributing greatly to liquidity and the easy-money policies that have prevailed since 2009.

For all this period, the Fed repeatedly stated that it would at some point “normalize” the balance sheet, presumably by returning the Fed’s total assets to a level at least somewhat close to its pre-2008 levels below $1 trillion.

Many skeptics of Fed policy frequently wondered aloud when this normalization would take place. It never did. The only period that approached “normalization” was a short-lived stint of minor reductions during 2019. Since 2020, of course, the balance sheet has only exploded upward as the Fed entered into a frenzy of asset buying to prop up asset prices during the 2020 economic crises. The Fed also continued to buy up large amounts of government bonds, thus pushing up bond prices. This has been critical in keeping interest on government bonds low as the federal government has amassed trillions of dollars in new debt over the past two years.

The FOMC’s New Plan

Now, after more than a decade of immense growth in the balance sheet, the Fed says that it will start reducing its assets. At Wednesday’s post–Federal Open Market Committee press conference, Fed chairman Jerome Powell announced cuts to the balance sheet to begin in July, and accelerate after three months.

But here’s the catch: the Fed’s announced steps are so timid, that even six months from now, there will be virtually no meaningful difference in the total size of the balance sheet. Moreover, if the economy goes into a downturn, we would expect the Fed to abandon normalization and turn to increasing the balance sheet yet again.

In other words, unless the Fed makes some big changes, the nearly $9 trillion in newly created Fed money isn’t going anywhere, and the Fed isn’t doing anything significant to reverse the immense monetary inflation of the past decade.

To illustrate this, let’s look at what the balance sheet will look like at the end of this calendar year, assuming everything goes according to the Fed’s plan.

First, here’s the plan. According to the Fed’s press release this week:

The Committee intends to reduce the Federal Reserve’s securities holdings over time in a predictable manner primarily by adjusting the amounts reinvested of principal payments received from securities held in the System Open Market Account (SOMA). Beginning on June 1, principal payments from securities held in the SOMA will be reinvested to the extent that they exceed monthly caps. …

For Treasury securities, the cap will initially be set at $30 billion per month and after three months will increase to $60 billion per month. The decline in holdings of Treasury securities under this monthly cap will include Treasury coupon securities and, to the extent that coupon maturities are less than the monthly cap, Treasury bills.

For agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities, the cap will initially be set at $17.5 billion per month and after three months will increase to $35 billion per month.

These cuts amount to very small changes.

As we can see in the first graph, the balance sheet as of May 2022 is at $8.9 trillion. The graph also shoes a hypothetical balance sheet through the end of the year. If the Fed does indeed begin making the cuts as proposed, beginning in June, the balance sheet will decrease by a total of 37.5 billion in the first three months, and 95 billion after that. So, but December, the balance sheet will have fallen to about $8.3 trillion. That’s where the balance sheet was back in August 2021. And how long would it take—under this plan—to return to the balance sheet that existed right before the Fed began its covid buying frenzy? About 46 months, or four years.

Of course, if experience is any guide at all, there is approximately a 0 percent chance that the Fed will stick to a quantitative tightening plan that lasts 46 months. Even the odds of doing it for the rest of this calendar year are very small, given that the economy contracted in the first quarter and the signs of a weakening economy are everywhere.

Also expect the political needs of the regime to take over if tax revenues begin to slip. As we’ve shown here on mises.org before, the Fed’s bond purchases play an important role in keeping the federal government’s debt service payments low. The Fed has been able to back off on this role in recent months as inflation-fueled tax collections have surged. But if we see tax revenues begin to fall, expect the federal government to demand the Fed once again facilitate deficit financing by buying government bonds.

So, both economic and political factors are very much against any true quantitative tightening taking place.

We can see the unlikeliness of quantitative tightening (QT) if we look at interest rate policy as well. The Fed announced on Wednesday a new fifty-basis-point increase to the target federal funds rate. That brings the overall target rate to 1.0 percent. The Fed also suggested it could continue with several 50 bp increases throughout the year. Powell also stated that it was not considering any 75 bp increases at this time.

So, assuming the Fed increases the target rate by 50 bp every month through the end of the year, that would still only bring the target rate to 4.5 percent.

What are the odds of that happening? The chances are very small. Yes, it is impressive that the Fed increased the target rate by 50 bp at all. Prior to this week, that hadn’t been done since the year 2000. But what are the odds of another seven increases of 50 bp for the rest of the year? Well, that’s virtually unheard of, and you’d have to go back to the days of Paul Volcker to see anything like it.

Why Have They Not Acted Until Now?

Some people who have a lot of confidence in the Fed as an institution might interject that maybe Powell is the next Volcker, and the Fed will boldly act to bring down inflation. But this raises an important question: if Powell is the new Volcker, why has he done nothing until now?

Inflation has been surging since Spring of 2021 and Powell’s Fed chose to do nothing except repeat bromides about inflation being transitory. It wasn’t until last month that the Fed finally increased the target rate to 0.5 percent. And through it all, the balance sheet only got bigger as the Fed refused to do anything at all resembling quantitative tightening. So, if the Fed has done nothing for the past year, why should we expect it to do something now?

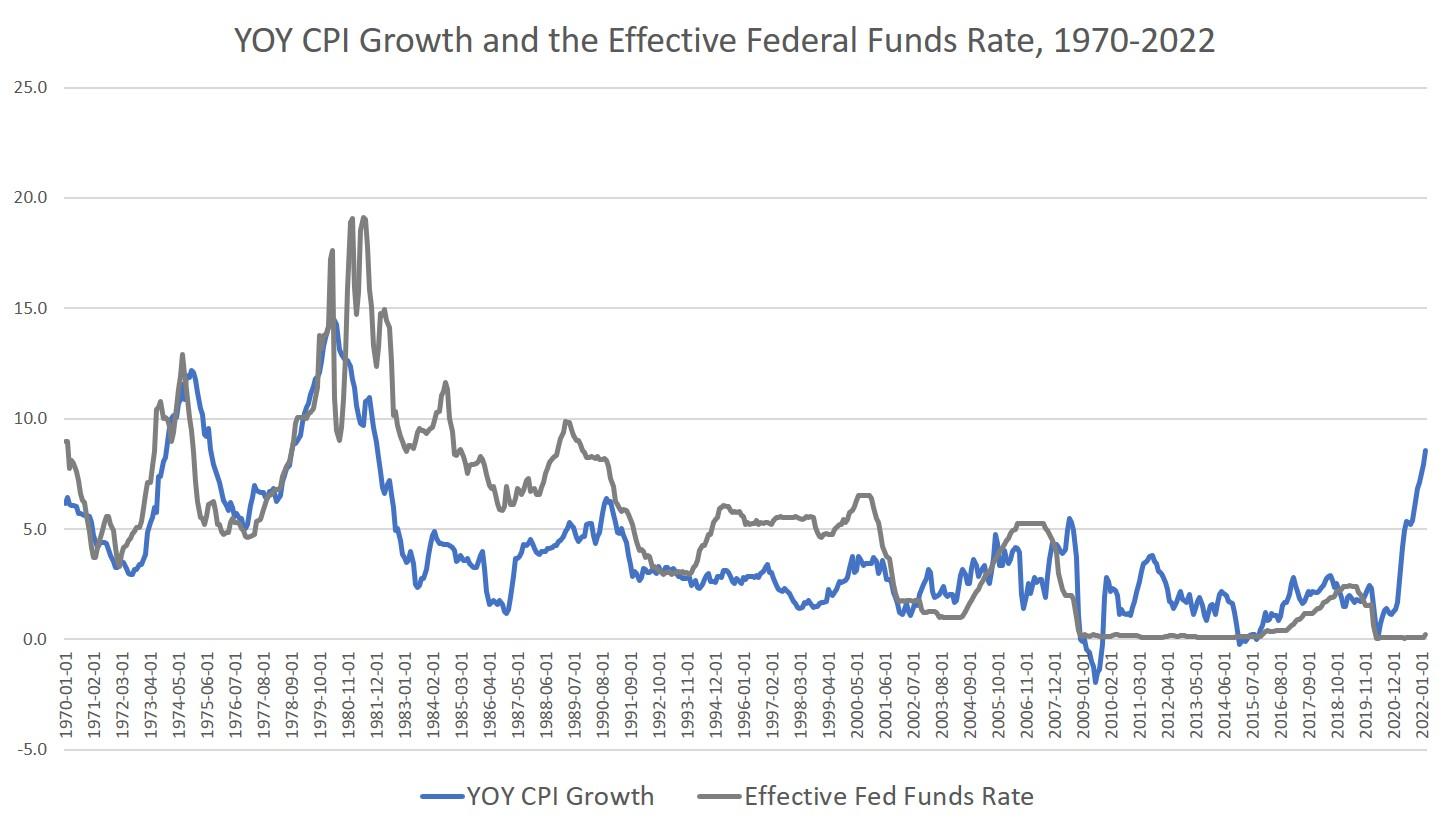

Indeed, to get a sense of how far behind the curve the Fed is on this, we can look at inflation growth versus the target federal funds rate. Even in the late seventies, before Volcker got going on his tightening spree, the target rate was still at least keeping up with year-over-year inflation rates. Meanwhile, in 2021 and 2022, the target rate is essentially flat while inflation has risen to a forty-year high. This is a not a group of central bankers that has a plan or the guts to implement it.

Apparently, Powell knows this. At the Q&A session following Powell prepared remarks yesterday, Powell’s tone was one of caution and a lack of confidence that Fed policy would actually rein in inflation. When asked by the Washington Post’s Rachel Siegel when people can start to see the results of tightening on inflation, Powell dodged the question and instead simply said that the process of bringing inflation down will be an unpleasant one.

Moreover, when asked how likely it is that the Fed’s policies will trigger a recession, Powell stated he’s still hoping for a “softish” landing.

In other words, the whole process is just a guessing game for the Fed. During the Q&A, Powell also refused to name what he thinks a neutral interest rate would be right now, and he was careful to state that the whole plan assumes “conditions evolve with expectations.” That is, if anything unexpected happens, all bets are off. And then we’re sure to see a new aggressive round of inflationary policy in the midst of economic weakening and forty-year inflation highs.

This is the Fed in 2022. The whole “plan” is to try some mild tightening and pray that things work out.