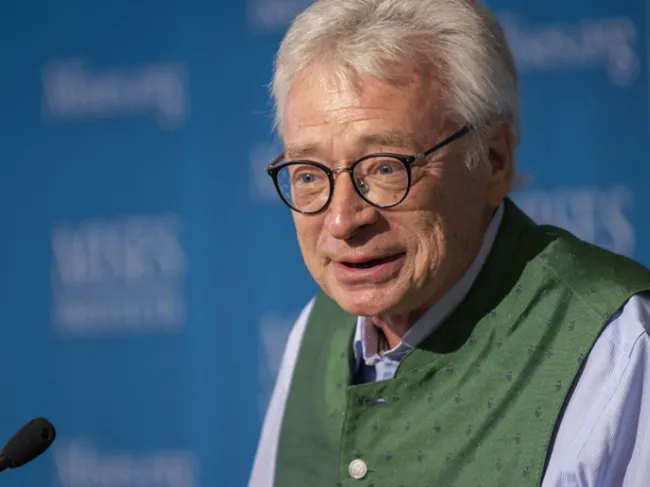

[Presented at the “Panel on the Significance of Hans Hermann-Hoppe” at the 2019 Austrian Economics Research Conference.]

I will recount a single episode which epitomizes Hans Hoppe’s singular approach to economic controversy.

On May 14, 2009, a Mises Daily piece appeared by Hoppe entitled “The Yield from Money Held’ Reconsidered”. It was the text of a lecture which had been presented as The Franz Cuhel Memorial Lecture in Prague the previous month.

The title of Hoppe’s lecture is a nod to William Hutt’s article “The Yield from Money Held,” published in 1956. In his article, Hutt argued that holding money was productive and generated a positive yield to the individual cash holder. Hutt proceeded mainly by criticizing the contrary position widely held by economists from John Locke and Adam Smith to John Maynard Keynes. The Smith-Keynes position maintained, according to Hutt, that “money is ‘barren,’ ‘sterile,’ ‘unproductive,’ ‘offering a yield of nil’”: “that it differs from other assets in that it is ‘dead stock.’” Although Hutt demolished the view that money is not a productive asset, he never explained exactly why holding a cash balance is productive. The aim of Hoppe’s lecture was to positively demonstrate that money held in cash balances is productive and to describe the unique nature of its productivity. In so doing, Hoppe filled the gap in Hutt’s argument and made an important contribution to monetary theory.

I will briefly outline Hoppe’s argument. Its point of departure is Mises’s original insight presented in Human Action that the need to hold money would not exist in general equilibrium, or what Mises preferred to call the “Evenly Rotating Economy” (ERE). In this world of perfect certainty, everyone would know the precise future dates and amounts of his expenditures and receipts. Each person would, therefore, immediately lend all the funds he received for terms that ensured that the loans came due on the dates the funds were needed. The demand for money would thus disappear in the ERE. Mainstream general equilibrium theorists, by the way, did not fully grasp this point until Frank Hahn brought it to their attention in 1965, 16 years after the publication of Human Action.1

Hoppe argues that the logical implication of Mises’s “fundamental insight” is that in the real world of uncertainty “the investment in money balances must be conceived of as an investment in certainty or an investment in the reduction of subjectively felt uneasiness about uncertainty.” Hoppe goes on to elaborate this point by emphasizing that money, by virtue of being “the most easily and widely salable good,” is also “the most universally present — instantly serviceable — good . . . and, as such, the good uniquely suited to alleviate presently felt uneasiness about uncertainty.” I might note here that Hoppe’s characterization of money as a uniquely ever present and immediately serviceable good has been unduly neglected or even explicitly disputed by some Austrians.2

For Hoppe it follows, then,

In holding money, its owner gains in the satisfaction of being able to meet instantly, as they unpredictably arise, the widest range of future contingencies. The investment in cash balances is an investment contra the (subjectively felt) aversion to uncertainty. A larger cash balance brings more relief from uncertainty aversion.

Defining the concepts of risk and uncertainty in the Knight-Mises sense, Hoppe then traces out the differing effects on the demand for money which result from the actor’s attempt to mitigate the disadvantages of risk and uncertainty, respectively. A greater aversion to risk prompts households and businesses to spend more money on insurance. This would either decrease the demand for money or leave it unchanged, depending on whether the funds to pay the premiums were withdrawn from consumption, saving, or cash balances. An intensification of uncertainty aversion, in contrast, would lead to an increase in the demand to hold money and therefore a reduction in spending on consumers’ goods or investment assets or both. As Hoppe puts it:

The sum of money that [a man] spends on insurance is an indication of the height of his aversion to risk. Insurance premiums are money spent , not held, and are as such, invested in the physical production structure of producer and consumer goods. The payment of insurance reflects a man’s subjectively felt certainty concerning (predictable) future contingencies (risks). . . . In distinct contrast, insofar as a man faces uncertainty he is, quite literally, not certain concerning future contingencies, i.e., as to what he might want or need and when. . . . Only money, on account of its instant and unspecific wide-ranging salability, can protect him against uncertainty.

Hoppe concludes:

To invest in cash balances means, I am uncertain about my present and future needs and believe that a balance of the most easily and widely saleable good on hand will best prepare me to meet my as-of-yet unknown needs at as-of-yet unknown times . [Emphasis is in the original]

In addressing this important issue in monetary theory, I believe Hoppe advanced beyond what Hutt, Mises, and Rothbard had written on the issue.

But this is only a part of the story I want to tell—and not the most interesting part. Hoppe’s article, which was focused on an arcane point of monetary theory, almost immediately ignited a firestorm of controversy that started on other economics blogs and spilled over to the Mises Economics Blog. Remarkably, the controversy had absolutely nothing to do with Hoppe’s main thesis. Rather, the uproar concerned preliminary remarks that Hoppe made consisting of two brief paragraphs totaling five sentences. But these incidental remarks touched the third rail of Austrian economics—they challenged a tenet of modern free banking orthodoxy.

In introducing his topic Hoppe had used the free bankers as one example of those monetary theorists who fail to grasp the unique productivity of money held. Hoppe wrote that, according to the free banking school, “an unanticipated increase in the demand for money ‘pushes the economy below it potential’ and requires a compensating money spending injection from the banking system.” He commented on this view, “Here it is again: an excess demand for money . . . has no positive yield or is even detrimental; hence help is needed.” Hoppe was careful to specify that, according to free bankers, this “help” would be forthcoming from freely competitive fractional-reserve banks. Hoppe concluded that, for free bankers, “the holding of (some, excess) money is unproductive and requires a remedy.”

The day after the publication of Hoppe’s piece, Larry White criticized it on the economics blog The Division of Labor. The sole focus of White’s post was Hoppe’s peripheral comment on the free banking school. White accepted Hoppe’s characterization of the free banking school’s position regarding the negative impact on employment and real output of an increase in the demand for money uncompensated by an equal increase in the supply of money. But he contended that Hoppe’s second paragraph contradicted the first and was nonsensical. The gist of his argument was that Hoppe’s critique of the free bankers confused the concept of an “excess demand for money”—conventionally understood by monetary theorists as a shortage of money—and the concept of excess cash balances held. White concluded that the free bankers’ concern about “macroeconomic difficulties” stemming from an “unsatisfied demand to hold money” did not contradict Hutt’s point that money is always held because it produces services to the holder.

Later that day Steve Horwitz posted a response to Hoppe on The Austrian Economists blog, edited by Steve and Pete Boettke among others. Steve quoted long excerpts from Larry’s post before concluding on a nasty note by asserting “Hoppe does not understand a concept that is central to monetary theory and even more central to the debate between free bankers and 100 percent gold advocates.” With that the flood gates opened and 87 comments on the topic were posted on the Austrian Economists blog from May 15 to May 21. Many of the comments came from Hoppe supporters, and Horwitz and Selgin intervened with their own comments a number of times to stamp out the dumpster fires of dissent that repeatedly flared up.

In the meantime, after enjoying the polemical fireworks for a few days, I posted a defense of Hoppe and critique of White and Horwitz on the Mises Economics Blog on May 18. My response to White was that Hoppe’s unconventional terminology did not invalidate his substantive argument. Even if Hoppe used the term “excess demand for money” irregularly to mean excess cash balances held, his point still held. Absent an exactly offsetting increase in the money supply, free bankers believed—and White admitted this—that the increased cash balances initially accumulated by those demanding to hold more money would precipitate a time-consuming process of a rising purchasing power of money. However, because all prices do not instantly adjust downward, according to free bankers, this process would engender a reduction in real output and employment, that is, a recession. It is in this sense that Hoppe meant that free bankers viewed the extra cash balances accumulated by those who first cut their spending as having “no positive yield” and as “even detrimental.” In other words, the current demand for money held was in excess of the demand which was consistent with potential output and full employment at the current price level .

My response to Horwitz was directed at two rhetorical questions he posed at the end of his post:

My questions now are: do the other Rothbardian critics of free banking really understand the concept [of the excess demand for money]? And why should anyone now take seriously any criticisms Hoppe makes of free banking?

I regret now that I lost my temper and responded quite uncharitably to his queries. Here is what I wrote:

Steve, my answers are: 1.The Rothbardian critics you address went to real graduate schools like Columbia, Rutgers, VPI, Berkeley, etc, and do not need a Heyne-level lecture from you on the meaning of excess demand for money or for anything else. 2. Ludwig von Mises made an elementary error in arguing that a competitive price can be distinguished from a monopoly price on the free market, therefore we should not take seriously anything else Mises ever wrote about monopoly. Is this proposition true or false? (I will give you extra credit if you can identify the logical error entailed in the proposition.)

To his credit Steve apologized for his impertinent questions in a later post. Anyway, after my post on May 18, the Mises blog blew up, with 94 comments posted by May 20. As the only academic economist defending Hoppe, I subsequently posted 3 additional comments responding specifically to Selgin, Horwitz and White, who had in the meantime posted comments on the Mises blog. George posted 8, Steve 5 and Larry 1. Most of the comments by George and Steve were in response to vociferous Hoppe fans who were fired up by my initial post. In the meantime my post instigated even more dissenting comments by Hoppeians over on the Austrian Economists blog, whose polemical tone understandably irritated George, Steve and Larry and elicited even more posts from them. I’ll read just two of the more humorous and provocative pro-Hoppe comments:

1. Well Steve, both Larry and you have been shown to be in error by Joe Salerno over at Mises. You are beating on a straw man characture [sic] of Hoppe’s position, not the real thing.

2. Does anyone have a link to that Salerno piece? I have no memory of Salerno often being wrong on monetary matters.

Now I was cited as the eminence grise in several of the pro-Hoppe posts because, as I mentioned, I was the only academic economist who defended Hoppe. But this raises the question: Where was Hoppe in this controversy? What and where were his comments? Hoppe in fact remained completely silent during the brouhaha that his article created and has not, as far as I know, said a word about it since. And therein lies his unique approach to economic controversy. It is the intellectual equivalent of the great Muhammad Ali’s rope-a-dope technique in boxing. State your position once, then lay back and let your opponents punch themselves out attacking it. In the end, your position is still standing.

- 1F.H. Hahn, “On Some Problems of Proving the Existence of an Equilibrium in a Monetary Economy,” in F.H. Hahn and F. P. R. Brechling, The Theory of Interest Rates: Proceedings of a Conference Held by the International Economic Association . New York: St. Martin’s Press, Inc. (1965), pp. 126-35.

- 2Willaim Barnett II and Walter Block, “Money: Capital Good, Consumers’ Good, or (Media of) Exchange Good?,” in Annette Godart-van der Kroon and Patrick Vonlanthen, eds., Banking and Monetary Policy from the Perspective of Austrian Economics , Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG (2018), pp. 49-64.