In recent decades, India has become a frontrunner in global politics representing a powerful bloc of emerging economies that are characterized by high growth rates and an untapped reservoir of human capital. It plays a crucial role in influencing international markets as its borders encapsulate not only some of the brightest minds in a wide array of specialties but also an increasingly unrestricted market that welcomes innovation and celebrates novelty. This historic transformation however came as a reaction to the centuries of colonial exploitation followed by severe stagnation in the decades succeeding independence. By the end of the 20th century, the Indian economy embraced the indispensable and almost inevitable reformation that led to increased economic development.

Prior to this economic reform, the country was plagued with mounting unemployment, acute inflation, and stagnation of economic activities. The government followed a system of five-year plans which dictated the flow of funds to individual sectors. The majority of public expenditure was diverted to the agricultural sector as this constituted a bulk of the nation’s exports. Inflation touched double-digit figures and severely affected the poorest sections of society. The annual GDP growth rate was dismal while the share of exports and imports constituted a meager portion of the overall GDP. The table below depicts these indicators in the period prior to 1991.

The New Industrial Policy, 1991

In 1991, the Minister of Finance Dr. Manmohan Singh proposed a ground-breaking policy that redefined the nature of public finance in India. The “LPG” Policy was based on three pillars — Liberalization, Privatization, and Globalization. The aim of the policy was to open the Indian economy to the foreign market in order to stimulate investment and growth. Under this policy the government reduced the number of industries reserved for the public sector from seventeen to just three. During the years prior to the reform, a “License Raj” system (translated as “Rule of the License”) was followed which comprised of an elaborate mechanism of regulations that were to be adhered to in order to set up business in the country. After 1991 however, the “License Raj” system was replaced by deregulation which made it easier for foreign companies to set up businesses in India. Tariff rates were reduced to encourage global trade and foreign direct investment was permitted in several sectors including banking, insurance, retail, and many more.

The figure below shows the changes in the Indian economy as a result of the “New Economic Policy” of 1991. It can be seen that in the period after 1991, the GDP growth rate demonstrates an upward trend while inflation is steadily reducing. The share of exports in the GDP also improved while foreign direct investment is gradually increased.

Source: World Bank Development Indicators, World Bank

Labour Market Reforms and Capital Mobility

The government took active steps to restructure the labour market and improve capital mobility in order to create a healthy investment climate. The labour market can be divided into two segments on the basis of institutionalization — the formal sector and the informal sector. In India, approximately 90 percent of employment is in the informal sector and this sector contributes more than 50 percent of the GDP. Organizations prefer to remain in the informal sector because of the high cost of formalization. The process of institutionalization includes a series of compliance costs and procedural regulations. In addition to this, stringent labour market regulations de-incentivize foreign investors as the cost of labour increases. In order to eradicate this problem the government introduced a series of reforms in the labour market beginning with deregulation in order to increase the ease of doing business within the country.

Capital mobility refers to the flow of capital across borders. With perfect capital account convertibility, financial integration can be achieved along with a reduction in the cost of acquiring capital. The Indian capital account was made more flexible as restrictions on inflow and outflow of capital were relaxed. Currently, the rupee is partially convertible in the capital account but the central bank is confident about achieving perfect mobility in the near future. The steady growth of the SENSEX indicator stands testament to this as India has become more receptive to capital market exchanges with the rest of the world in the form of institutional and direct investments.

Source: SENSEX indicators, Bombay Stock Exchange

Impact of the Economic Reforms

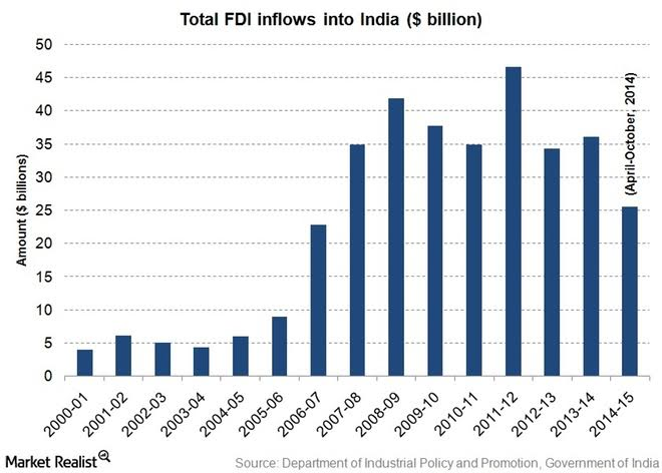

The impact of the economic reforms was seismic as it encompassed all sectors of the economy. India soon became a leading market for a multitude of foreign goods in the form of consumer products and investments ranging from retail to information technology. Foreign networks were introduced in the media sector which was originally reserved for the government. The telecom sector expanded resulting in increased access to communication technology. The availability of cheap labour led to a number of foreign firms outsourcing jobs to the Indian market which consequently boosted domestic employment rates. Multi-national corporations were allowed to set up subsidiaries in India which flooded the market with a variety of quality consumer goods at competitive prices.

Source: Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, Government of India

The influx of foreign investment resulted in the growth of consumerism in India as the ultimate beneficiaries of such liberalization measures were the domestic residents of the country. They were now able to reap the benefits of quality products at cheap prices and serve as the primary market for foreign brands in various sectors like retail, automobile, and service providers. The open economy paved the way for the introduction of foreign corporations that facilitated cheaper methods of production, more efficient technologies, and most importantly endowed the consumer with the privilege of “choice.“ Domestic producers were forced to compete with these increased standards and were consequently given further impetus to innovate and adapt to the changing business environment. Through the integration of the domestic market with the global market, both producers and consumers stood to profit with increased access to technology and connectivity as well as lower prices, among other benefits of higher employment and raised standards of living.

Although there is growing talk of limiting free trade in the developed world, India serves as a striking example of an emerging market that has overcome the shackles of protectionism as it moves toward becoming a powerful global economy.

Trisha Mani is a final year undergraduate at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai. She aims to pursue a career in the field of economics and its applications.