The media has again begun focusing on the fact that most Americans surveyed have less than $1,000 in their savings accounts. On Sunday, USAToday reported on “America’s spend-first mentality” and last week, CNBC suggested that 34% of Americans “have no savings at all.”

The statistic that most Americans have less than $1,000 in sort of liquid emergency fund stems from a 2015 study by GoBankingRates which concluded that 34% of Americans have zero dollars in a savings account while 35% have between one dollar and $1,000 dollars.

For those who have little in a savings account, this doesn’t mean their net worth is necessarily zero or negative, of course. Some of those people own property (such as real estate and securities) outside their savings account.

Nevertheless, the implication is that most Americans can’t even deal with a small $500 automobile and health care bill in an emergency.

For a country that has one of the world’s highest levels of disposable income, this is a grim figure.

CNBC even goes on to note in a September 2016 article that, according to a study by the Economic Policy Institute, the median retirement savings among all American families is a measly $5,000.

Are Americans Worse Savers than Everyone Else?

It is often suggested that Americans are particularly bad savers. Americans spend everything they’ve got we are told (although it is often admitted that in decades past, Americans saved at considerably higher rates). Or, when there’s a political agenda to be nourished, we might be told that Americans can’t save anything because they have to spend every last dime on health care.

In a past article on international comparisons of net worth, I examined the claim that Americans can’t save because of the lack of a more “generous” welfare system. This is unconvincing. While Americans certainly spend more on health care out-of-pocket, its also true that Americans also buy bigger houses, drive more luxurious cars, buy houses sooner, rent apartments sooner, and go to college more than many European societies. In other words, Americans really do like to spend more on many things other than health care.

While Americans are famous for spending, in neither net worth nor household savings is the US at the bottom of the heap. Indeed, in terms of household savings, the US is near the middle:

According to OECD data, the US had a household savings rate of 5 percent in 2014, which places it higher than the EU overall (3.8 percent) and higher than Canada.1

There’s nothing remarkable about the US in these figures, and it’s certainly hard to say the US is any sort of outlier in this regard.

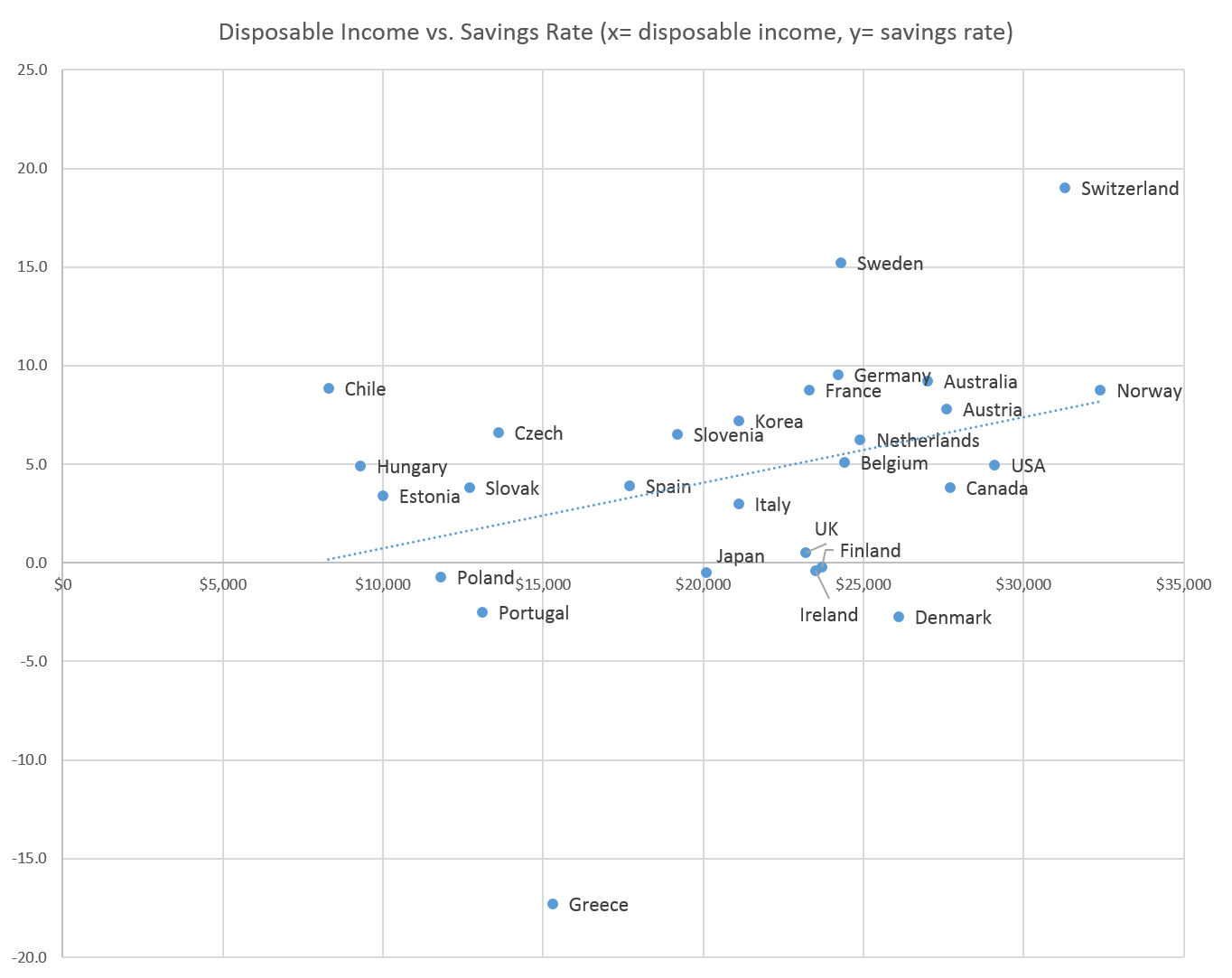

However, if we start to look at savings rates in the context of disposable income, we do find that Americans do save quite a bit less than in countries with comparable levels of disposable income.

The next graph shows savings rates in light of disposable income levels. The US is among the countries with the highest income (taking into account taxes and social benefits payments), but is only in the middle in terms of savings rates2 :

This should be the case since, presumably, households with higher incomes are able to save more. In other words, once a household’s income begins to exceed the cost of daily necessities, one should expect that household to begin to save some of the surplus. The higher incomes go above these basic levels — ceteris paribus — the higher the savings rate would tend to be. The same claims could reasonably be made about a region, metro area, or country. Those areas with higher incomes could be expected to have higher savings rates.3

Nevertheless, the US lags well behind other wealthy countries like Norway and Switzerland in terms of savings.

Why is this? Well, part of this comes back to our earlier analysis. Americans simply like to spend more on SUVs and houses with three-car garages.

So far, though, we’ve only looked at static 2014 numbers for international comparisons. When we look at some international trends over time, we find not only that Americans are saving more than you’d expect — compared to the last twenty years — but that Americans seem to be in more of a saving trend than many others in wealthy countries.

First of all, let’s look at US savings rates over the past 20 years.

According to the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, the personal savings rate in recent years is not especially low in light of recent decades. It is certainly down from where it was back in the 1970s and 1980s, but it is up from what we saw during much of the 1990s and 2000s:

So, we can conclude that the savings rate, while low by broader historical standards, is not low in terms of recent history. Indeed, as was mentioned more than once at the time, the savings rates during the middle of the last decade were at levels not seen since the Great Depression when people were exhausting their savings to make ends meet. In 2005, though, the US was not in recession, and yet savings rates were at exceptionally low levels.

Central Banks and Saving Rates

Much of this was due to a combination of an expanding economy and historically low interest rates. By 2004, after more than 25 years of declines, the effective federal funds rate hit 1 percent. At the same time, mortgage rates were falling below six percent for the first time in decades. For many, it also seemed that the economy was rock-solid. When it’s easy to borrow money at remarkably low interest rates, and when the economy seems very good, few are motivated to save.

Even after the Fed allowed interest rates to creep up again from 2004 to 2007, interest rates were still at levels below what had been seen in most of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. It was only in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008 that savings rates really began to climb again, hitting a 15-year high of 7.6 percent in 2012.

This has been vexing for the Federal Reserve since the central bank believes that economic growth can be achieved by reducing saving and increasing spending. Historically, reducing interest rates has spurred spending and borrowing and reduced saving. After all, why bother saving anything when bank deposits will collect almost nothing in interest and borrowing is easy?

In a recent article for mises.org, Victor Xing examined why lowering rates isn’t working to reducing saving anymore. In an environment of uncertainty, savers become more cautious, and will respond to low interest rates by saving even more. If savings accounts are going to pay almost nothing, savers figure, then they need to save even more than they would have otherwise.

It seems that for all its calming talk about “moderate growth” the Fed has not been able to convince people that things are getting better. If anything, savers have become more cautious and saving in spite of the fact that saving will earn them virtually no return at all.

The Nuclear Option: Negative Rates in Europe and Japan

Thus, the Fed’s ultra-low interest rates have failed to eliminate saving in the United States.

In fact, it seems that over the last two or three years that Americans have become slightly more inclined toward saving than many other wealthy countries.

The next graph compares the past 15 years of saving rates for seven countries and the EU. We find that in some places, such as Italy and Japan, the saving rate has collapsed over this time period. As late as the 1990s, the Japanese were noted for saving much more than many other populations. By 2013, though, the saving rate in Japan had fallen to zero percent, and as of 2014, went negative. In Italy, the saving rate fell from 16.5 percent in 1996 to 3 percent in 2014.

During this period, the euro zone adopted the euro currency, changing the dynamic of monetary policy throughout Europe. However, as has been the case in the UK, Japan, and the US, the euro zone has moved toward lower interest rates and easy money.

In the EU overall, since 2002 when the euro became commonly-used legal tender throughout the EU, the saving rate has been cut in half.4

Meanwhile, in the UK, continued easing of monetary policy on the part of the Bank of England has helped move the saving rate from 7 percent in 1997 to 0.5 percent in 2014.

Viewed in light of these comparisons, the saving rate in the US looks relatively stable, if perhaps not as stable as the saving rates found in Germany and France.

In some cases — i.e., the US, Canada, and the UK — saving rates appear to be either flat or increasing since 2008, in spite of continued efforts to force more spending via dovish monetary policy. The exceptions appear to be the areas where central banks have crossed over into use of negative interest rates. In the euro zone overall, saving rates continue to fall, and in Germany, France, and Italy, saving rates are either flat or falling.

Certainly, Americans should be saving more. Saving, after all, is what leads to true wealth production, capital accumulation, and economic growth.

The central bankers of the world disagree, though. They want more spending and less saving. And, until recently, it was clear that central banks have largely been successful at pushing down saving rates. Yet, as incomes have stagnated over the past 15 years, these declines in saving have not produced the sort of economic growth the central banks hoped they would.

For their part, Americans may have noticed they’re not getting richer, and rising saving rates may reflect a realization by Americans that they’ll need to start saving money if they’re even going to retire. This is bad news for the Fed, of course, which wants Americans to spend every last dime in what is a vain search for growth. Will the Fed then turn to negative rates and other radical tactics in an attempt to goad more spending? We may find out soon.

Ryan McMaken is the editor of Mises Wire and The Austrian. Contact: email, twitter.

- 1The disposable income data can be found here: https://mises.org/blog/why-do-americans-have-such-high-incomes-and-so-little-savings

The OECD savings data can be found here: https://data.oecd.org/hha/household-savings.htm#indicator-chart - 2The disposable income data is from the OECD’s “Society at a Glance” report: http://www.oecd.org/els/societyataglance.htm

- 3There is clearly a correlation here between income and saving, although thanks to a variety of cultural factors, it is not exactly the most robust correlation and certainly not a 1-to-1 relationship. The r-squared value for the scatter plot is 0.064. In any case, the US should at least be on the trend line, if not above it.

- 4The following graph is built using the same OECD data as above.