That Austrians and Keynesians do not share many views on economics (or probably anything else) is obvious, so a difference of opinion between the two hardly should surprise anyone. However, it still is important to point out the differences between the two camps, especially at the current time when Keynesians are all the rage in Washington (When did they ever leave?) and especially in the Joe Biden administration and, of course, the editorial pages of the New York Times.

Perhaps there is no greater difference between Keynesians and Austrians than their beliefs on economic booms. In short, Keynesians believe that all policies should promote the booms and even when they crash, that government should employ all means to continue the boom. Austrians, on the other hand, see booms as times when massive malinvestments pile up until the whole unwieldy system no longer can stand, leading to the inevitable crashes. In short, Keynesians claim that booms should be the goal of economic policymakers while Austrians see them as wasteful, dangerous, and ultimately destructive.

As noted before, Keynesians definitely hold the official reins of governmental power and also are the darlings of the mainstream media. Janet Yellen, US secretary of the Treasury, is a Keynesian. Chairman of the Federal Reserve System, Jerome Powell, is not a Keynesian by formal academic training but certainly has operated his office in the spirit of Keynes. And the loudest Keynesian shill, Paul Krugman, wields much influence from his perch at the NYT. Austrians, on the other hand, are nowhere to be found in the reaches of government nor in the influential corporate office and certainly not on Wall Street.

If political and academic dominance were the arbiter of truth, then Keynesians are right, and Austrians are dangerously deluded. Keynesians have the raw numbers and the loudest and most powerful institutional voices. Austrians enjoy none of those perks.

A thousand Keynesians speaking with one voice, however, still are wrong about economic booms, and none is more mistaken than Krugman. In a recent column, “Who’s afraid of the big, bad boom,” Krugman presents the Keynesian view of economic booms and concludes that the end of all economic policies should be the initiation and sustaining of the boom. He writes:

There definitely is a boom underway, even if a vast majority of Republicans claim to believe that the economy is getting worse. All indications are that we’re headed for the fastest year of growth since the “Morning in America” boom of 1983–84. What’s not to like?

Krugman goes on to write that booms are not perfect and sometimes can lead to economic “bottlenecks” (such as the current spike in lumber prices), but such things are little more than temporary glitches to the happy world of prosperity for all, made possible by permanent spending sprees:

But do such bottlenecks pose a risk to overall recovery? Do they mean that policymakers need to pull back? No. The overwhelming lesson of the past 15 years or so is that short-term fluctuations in raw material prices tell you nothing about future inflation, and that policymakers that overreact to these fluctuations—like the European Central Bank, which raised interest rates in the midst of a debt crisis because it was spooked by commodity prices—are always sorry in retrospect.

So, pay no attention to the man behind the curtain. Commodity prices always fluctuate, boom or no boom, so if lumber prices go up and housing markets start to resemble to real estate bubble of the mid-2000s, that is the natural consequences of prosperity brought to you by loose monetary policies and increased government spending.

But what happens if the housing markets—and the stock markets—crash as they did in 2007 and 2008? In 2008, Krugman squarely laid the problem upon inadequate financial and economic regulation and claimed Ronald Reagan was responsible for the deregulation that created the mess. (Not surprisingly, Krugman also got it wrong on the history of deregulation, but like Bluto Blutarsky, who wrongly claimed that “the Germans bombed Pearl Harbor,” we can’t interrupt someone when he is on a roll.)

Since 2008 and the presidency of Barack Obama, things have changed drastically. This time there are no subprime mortgage securities cooked up by Wall Street geniuses and the federal government essentially nationalized the mortgage industry as a response to the meltdown, something that met Krugman’s approval. Furthermore, the government’s monetary policies of suppressing interest rates (ostensibly to fuel that Keynesian polestar, aggregate demand) have created the stock market bubble—that is the only thing we can call it—which has accelerated that “wealth gap” that Krugman claims is perhaps THE major economic problem this country faces.

(Krugman believes that we can both create stock bubbles and then alleviate the results through massive wealth and progressive income taxes, as both are forms of economic stimulation that encourage spending and discourage alleged “hoarding” by the rich. That is something for a future commentary.)

When this current boom crashes (as inevitably it will), one suspects that Krugman first will blame free market capitalism and claim that part of the problem is a lack of regulation, since everyone knows that since the advent of the Ronald Reagan presidency, there has been no government regulation of any markets. To Krugman and the Keynesians, it will be proof that markets cannot be trusted and further proof that market prices are little more than a right-wing plot by the intellectual descendants of Milton Friedman.

Once the blame game starts, then Krugman and other Keynesians will demand that government engage in various policies—and especially borrowing and spending—to bring back those lofty levels of so-called aggregate demand and the high prices that accompany such demand. This hardly is a new strategy. The original New Deal policies from Franklin D. Roosevelt (as opposed to the nearly identical New Deal policies from Herbert Hoover) were based upon the belief that falling prices were the main cause of the depression and that government needed to force up agricultural, commodity, and labor prices in order to right the economic ship. Thus, the government tried to cartelize the entire nonfarm economy through the National Industrial Recovery Act and prop up farm prices through the Agricultural Adjustment Act, both of 1933. In 2008, Martin Feldstein, President Reagan’s chief economic adviser, sounded the same horn on housing, declaring in The Wall Street Journal that the chief culprit of the 2008 meltdown was falling prices in housing:

A successful plan to stabilize the U.S. economy and prevent a deep global recession must do more than buy back impaired debt from financial institutions. It must address the fundamental cause of the crisis: the downward spiral of house prices that devastates household wealth and destroys the capital of financial institutions that hold mortgages and mortgage-backed securities.

One could write volumes about the economic fallacies contained in that paragraph, but readers get the point. In Keynesian land, there are no economic fundamentals, no relationships between factors of production, just spending. Spend enough money and policymakers can keep factors of production employed indefinitely; when the inevitable dislocations appear, paper them over with even more spending and let the good times roll and roll and roll.

Austrians, according to Krugman, are the authors of a very bad morality play when it comes to diagnosing and analyzing booms and busts:

The hangover theory (what Krugman calls the Austrian Business Cycle Theory) is perversely seductive—not because it offers an easy way out, but because it doesn’t. It turns the wiggles on our charts into a morality play, a tale of hubris and downfall. And it offers adherents the special pleasure of dispensing painful advice with a clear conscience, secure in the belief that they are not heartless but merely practicing tough love. Powerful as these seductions may be, they must be resisted—for the hangover theory is disastrously wrongheaded. Recessions are not necessary consequences of booms. They can and should be fought, not with austerity but with liberality—with policies that encourage people to spend more, not less.

Krugman wrote this more than twenty years ago but has not changed his views since then. Not surprisingly, he reduces accounts of malinvestment—in fact, he doesn’t even use that term, wrongly calling it “overinvestment” instead—to mere moral tut-tuts which actually are dangerous because Austrians, in Krugman’s view, malevolently urge people to stop spending at a time when increased spending is needed most. In short, booms are good, always good. Booms bring prosperity, and anything that discourages prosperity is bad, end of argument.

This analysis misjudges both booms and busts, which the current political and academic climate tends to reward rather than punish. (Robert Murphy goes into detail about Krugman’s errors in this article, one well worth reading.) If Krugman believes booms are good and should be maintained perpetually, then it is reasonable to believe that anything less that outright condemnation of a bust borders on being immoral. When that viewpoint is combined with Krugman’s increasing left-wing radicalism, it is not hard to understand his unrelenting hostility to Austrians and their viewpoints. When he first criticized the Austrian business cycle theory in 1998, his take was that Austrians were wrong, dismissively so, but he stopped there. Today, he wants readers to believe that Austrians are Evil People who want others to live in poverty and starve to death. We no longer are dealing with intellectual disagreements but rather a titanic battle between the Forces of Good and Evil and Krugman is on the side of Good. One cannot argue with anyone defending free markets and market prices because, in his words, “the mendacity is the message.”

Krugman’s radicalism notwithstanding, we still must deal with his argument that economic booms not only are desirable but that they can be sustained indefinitely with no resulting damage to the economy. This is not to say that a sustained boom contains no fluctuations; even Krugman admits that, but he also believes that government simply can make adjustments on the fly to even the rough places, something that requires the election of like-minded progressives that believe government can work near economic miracles.

Why, then, do Austrians hold that booms cannot be sustained? First, and most important, Austrians point out that the conditions that create the boom are not benign. Booms occur when monetary authorities (i.e., Federal Reserve System or some other national central bank) hold interest rates below market levels by expanding the supply of money for the purpose of expanding borrowing for business expansion. This increases the demand for capital goods (and factors of production associated with their creation) and puts new money into the hands of employees in those associated industries. The employees spend the money on consumer goods, creating new demand for those products.

(The best account of the Austrian theory is found in Murray N. Rothbard’s America’s Great Depression, whose first half Rothbard dedicates both to explaining the business cycle theory and also answering the Keynesian critics of the theory. One only wishes that Rothbard had lived long enough to respond to Krugman’s missives.)

With Keynesians such as Krugman, this process can go on indefinitely. True, some of the capital investments might not be sustainable, but that can be explained by the fact that there always are business fluctuations in the course of the economy. He writes:

But let’s ask a seemingly silly question: Why should the ups and downs of investment demand lead to ups and downs in the economy as a whole? Don’t say that it’s obvious—although investment cycles clearly are associated with economywide recessions and recoveries in practice, a theory is supposed to explain observed correlations, not just assume them. And in fact the key to the Keynesian revolution in economic thought—a revolution that made hangover theory in general and Austrian theory in particular as obsolete as epicycles—was John Maynard Keynes’ realization that the crucial question was not why investment demand sometimes declines, but why such declines cause the whole economy to slump.

Here’s the problem: As a matter of simple arithmetic, total spending in the economy is necessarily equal to total income (every sale is also a purchase, and vice versa). So if people decide to spend less on investment goods, doesn’t that mean that they must be deciding to spend more on consumption goods—implying that an investment slump should always be accompanied by a corresponding consumption boom? And if so why should there be a rise in unemployment?

In other words, even if some capital investments go south, there is no reason for the economy to decline. After all, money has not disappeared, so if spending is halted on some unsuccessful capital investments, then consumers can just spend more money elsewhere. The Keynesian Cross “proves” that aggregate expenditures and GDP are identities, so it really doesn’t matter if money is spent on capital goods or consumer goods since the results are the same.

Then what causes the economic downturn? Krugman has an easy answer:

A recession happens when, for whatever reason, a large part of the private sector tries to increase its cash reserves at the same time.

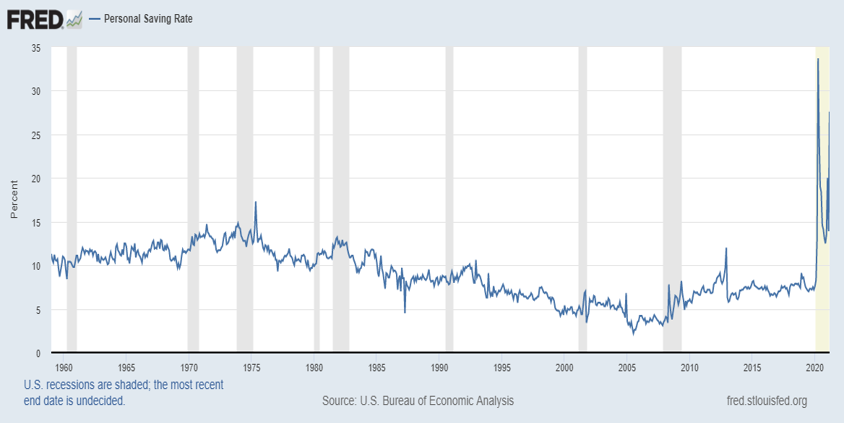

In other words, large-scale malinvestments really don’t matter; instead, it is the panicked consumer that decides in the face of economic uncertainty that saving money might be a good thing. Indeed, as Robert Murphy notes, US savings rates quadrupled from late 2007 to mid-2009 (from about 2 percent to 8 percent) so that would seem to verify Krugman’s causality. But it doesn’t.

To counter Krugman’s thesis, I go back to the Austrians but not Rothbard. Instead, I turn to Carl Menger, the “founder” of the Austrian school who begins the opening chapter in his groundbreaking Principles of Economics with:

All things are subject to the law of cause and effect. This great principle knows no exception, and we would search in vain in the realm of experience for an example to the contrary.

While these words hardly seem to refute anything, let alone Krugman’s stated cause of economic downturns, look again. Austrian analysis is monocausal, that is, there is a cause and an effect. Krugman’s theory (I assume he believes his theory is “settled science”) brings up an interesting question: Why do consumers suddenly cut back on their spending begin saving? Krugman never says.

It seems that one obvious reason is that consumers are unnerved about the economic downturn, but if Krugman’s statements about the breakdown of the boom are correct, then consumers would have no logical reason to be nervous. Perhaps Krugman might claim that those dastardly Austrians have fooled everyone into thinking that credit-fueled booms are unsustainable, so when someone goes out of business or some other economic indicator points downward, people panic and the Austrians then goad them into saving more money.

But why don’t consumers start spending again as soon as someone in Washington gives the equivalent of the “all clear” signal? After all, the Keynesian paradigm dominates in politics, the media, and in higher education. The notion of Austrians playing the role of Emmanuel Goldstein is a bit far-fetched, given the Austrians don’t have much of a media or political platform. How Austrians can scare an entire population into sabotaging the economy by increasing their savings lacks the authenticity of Mengerian causality.

When they look at the increase in savings, Austrians ask the following: Why the sudden increase in savings? In fact, if we look at US personal savings rates for the past sixty years, we see that savings rates do increase at some point in most recessions, but they increase during the recoveries, too, so there is no way one can draw a clear causal inference that moves from the growth in personal savings to a recession.

The monocausal view would lead us elsewhere. In Krugman’s world, people irrationally start saving, send the economy spiraling downward, and then it takes government—led by brilliant technocrats like Krugman—to spend and inflate the economy back into prosperity. To the Austrians, the notion of people suddenly stampeding to save their money for no visible reason in nonsensical. Furthermore, contra Krugman, saving money is not an irrational response to a perceived change in the economy. People don’t save in a vacuum; they save in order to be able to spend in the future, either for a major purchase or for times when their incomes are less than they are at present. In short, the evidence shows that people quickly change their saving habits in response to a crisis, as opposed to an increase in savings creating the crisis.

Krugman claims that even large-scale malinvestments really should have no overall effect, writing:

For if the problem is that collectively people want to hold more money than there is in circulation, why not simply increase the supply of money? You may tell me that it’s not that simple, that during the previous boom businessmen made bad investments and banks made bad loans. Well, fine. Junk the bad investments and write off the bad loans. Why should this require that perfectly good productive capacity be left idle?

The hangover theory, then, turns out to be intellectually incoherent; nobody has managed to explain why bad investments in the past require the unemployment of good workers in the present. Yet the theory has powerful emotional appeal. Usually that appeal is strongest for conservatives, who can’t stand the thought that positive action by governments (let alone—horrors!—printing money) can ever be a good idea.

Elsewhere, he states of the Austrian theory:

[T]his story bears little resemblance to what actually happens in a recession, when every industry—not just the investment sector—normally contracts.

His statements show ignorance in two areas: capital theory and the actual events of the business cycle. Rothbard corrects Krugman’s errors, first by pointing out that the crisis is characterized by what Rothbard calls a “cluster of (entrepreneurial) errors,” and then by noting that the downturns do not hit all sectors equally:

It is the well-known fact that capital-goods industries fluctuate more widely than do the consumer-goods industries. The capital-goods industries—especially the industries supplying raw materials, construction, and equipment to other industries—expand much further in the boom, and are hit far more severely in the depression.

This is important, as the crisis does not occur because people stop spending and then all business sectors shrink accordingly. The capital goods and related industries are likely to have the greatest number of malinvestments, so it stands to reason that they would be hit hardest in the crisis.

Krugman does make an interesting point: If the problem is just malinvested capital, why can’t workers make the quick transition back to employment in sectors not hit as hard? In fact, that often was what happened in previous business cycles. Thomas Woods writes of the 1920–21 recession that it was severe—and short. Writes Woods:

The economic situation in 1920 was grim. By that year unemployment had jumped from 4 percent to nearly 12 percent, and GNP declined 17 percent. No wonder, then, that Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover—falsely characterized as a supporter of laissez-faire economics—urged President Harding to consider an array of interventions to turn the economy around. Hoover was ignored.

Instead of “fiscal stimulus,” Harding cut the government’s budget nearly in half between 1920 and 1922. The rest of Harding’s approach was equally laissez-faire. Tax rates were slashed for all income groups. The national debt was reduced by one-third.

The Federal Reserve’s activity, moreover, was hardly noticeable. As one economic historian puts it, “Despite the severity of the contraction, the Fed did not move to use its powers to turn the money supply around and fight the contraction.”2 By the late summer of 1921, signs of recovery were already visible. The following year, unemployment was back down to 6.7 percent and it was only 2.4 percent by 1923.

In other words—contra Krugman—there was no intervention, no money printing, no jobs programs, nothing that Krugman claims are vital to bring economic recovery. If one realizes that this downturn came in the aftermath of World War I when the war-spending boom quickly contracted and accompanying the return of millions of soldiers was the Spanish Flu pandemic which killed 500,000 Americans (when the US population was 104 million, less than a third of the population today). Yet, the economy quickly recovered when the economy moved out of inflation-driven war goods production back into production commensurate with postwar needs.

Austrians do not question booms because they don’t like prosperity or because they have character defects. Rather, Austrians understand that booms involve lines of investment into areas of production that cannot be sustained, even when government throws even more money at them. What Krugman calls “perfectly good productive capacity” actually is malinvested capital that is idle for a reason.