Total public debt reached $34,001,493,655,565.48 at the end of 2023, with over $2.5 trillion added since the end of 2022.

The U.S. Treasury reported $6.1 trillion in outlays, but only $4.4 trillion in receipts for the 2023 fiscal year, resulting in a deficit of almost $1.7 trillion.

Figure 1: Cumulative receipts and outlays of the U.S. government

Source: U.S. Treasury, Monthly Treasury Statement, November 2023.

Interest payments on the debt skyrocketed in 2023 due to the combination of exorbitant spending and higher interest rates.

Figure 2: Federal government interest payments

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Federal government current expenditures: Interest payments [A091RC1Q027SBEA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, January 2, 2024.

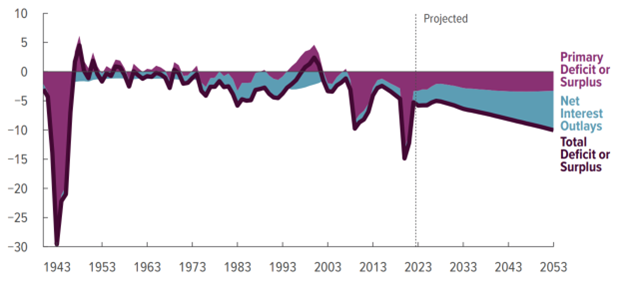

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that these interest payments will soon take up a majority of the budget.

Figure 3: CBO: Deficits as a percentage of gross domestic product

Source: The 2023 Long-Term Budget Outlook (Congressional Budget Office, June 2023), figure 1-1.

These trends are the source of much controversy in the economics profession. Austrian and free market-inclined economists claim that government spending is out of control and that the accumulated debt has been on an unsustainable path for many years. Others, including Keynesians and those in the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) camp, say that the debt is innocuous (”We owe it to ourselves!”) or even beneficial (”Public debt is private savings!”).

For example, Stephanie Kelton, MMT adherent and professor of economics at Stony Brook University, said this about the debt in a recent NPR interview:

Over the arc of U.S. history, the U.S. government typically spends on an annual basis more dollars into the economy than it taxes away from us. And so it’s adding dollars, and over time, we keep track of how many dollars have been added. And what that $34 trillion is telling you is that over the long sweep of history the U.S. government has put that many dollars into our hands without taxing it away. So what it is it’s our after-tax savings that’s being reported. So when you think about it like that, it really does kind of change your perspective. You say, “Well, should I be very worried about this large savings that has been accumulated?” And I think that leads us in a very different direction.

Kelton and other MMTers say that people have been worried about the debt for a long time—they are like Chicken Little, always claiming that the sky is falling. She says that the U.S. government will always be able to pay its debts because it can issue its own currency.

But this argument only addresses one part of the debt phenomenon. Of course the government can print money to pay its bills. Mises and Rothbard acknowledged this well before Kelton was born.

Mises also addressed the view of public debt as private savings:

The state, this new deity of the dawning age of statolatry, this eternal and superhuman institution beyond the reach of earthly frailties, offered to the citizen an opportunity to put his wealth in safety and to enjoy a stable income secure against all vicissitudes. It opened a way to free the individual from the necessity of risking and acquiring his wealth and his income anew each day in the capitalist market. He who invested his funds in bonds issued by the government and its subdivisions was no longer subject to the inescapable laws of the market and to the sovereignty of the consumers. He was no longer under the necessity of investing his funds in such a way that they would best serve the wants and needs of the consumers. He was secure, he was safeguarded against the dangers of the competitive market in which losses are the penalty of inefficiency; the eternal state had taken him under its wing and guaranteed him the undisturbed enjoyment of his funds.

According to Mises, there is a categorical difference between business investment and government bonds: one is subject to consumers and the other is not. There are tradeoffs in everything, and the tradeoff in eliminating risk in the form of government bonds is that the revenues which are used to pay back the creditors are taken by force—they are divorced from the consumer-satisfying and resource-economizing principles of the market. The bondholder is “no longer a servant of his fellow citizens, subject to their sovereignty,” but “a partner of the government which ruled the people and exacted tribute from them.”

Thus, the fundamental problem with the government’s debt is that it represents a terrible burden. Setting aside the question of default, the fact remains that no dollar spent by the government is subject to the consumers’ approval in the same way private businesses are tested daily. Dollars spent in excess of taxation are not “private savings.” Government spending is a drain on the economy because resources are channeled away from private enterprise, toward an institution that is immune to profit and loss. To the extent that the government’s debts are bought by its central bank, the problems are compounded in the form of inflation, business cycles, and a completely unrestrained government.